The Apportionment Problem

Brian Lins

Hampden-Sydney College

Monday, June 3, 2024

The Apportionment Problem

Here is what the Constitution says about how the seats of the House

of Representatives are to be apportioned to the states:

The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen

every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors

in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of

the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

No Person shall be a Representative who shall not have attained to

the Age of twenty five Years, and been seven Years a Citizen of the

United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that

State in which he shall be chosen.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the

several States which may be included within this Union, according to

their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the

whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a

Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all

other Persons.

What Does It Mean?

The wording here is vague. What does it mean that Representatives

shall be apportioned among the several States… according to their

respective Numbers?

From the beginning, it was understood that this means the number of

representatives should be proportional to the population of the state.

If a state is twice as big, it should have twice as many

representatives.

Proportional Representation is Tricky

The problem is, there are only 435 seats in the House of

Representatives. Those cannot be divided perfectly proportional to the

populations of every state.

The First Apportionment

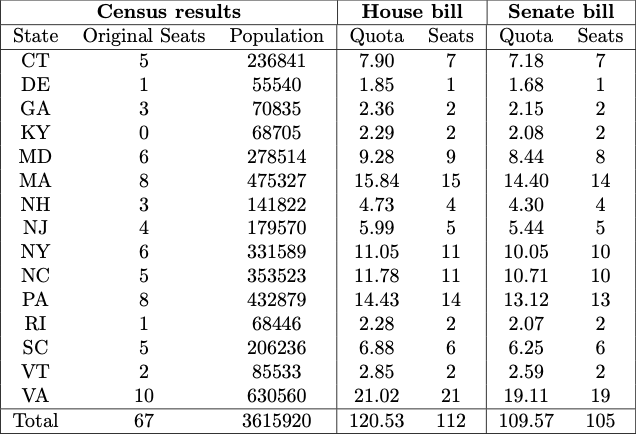

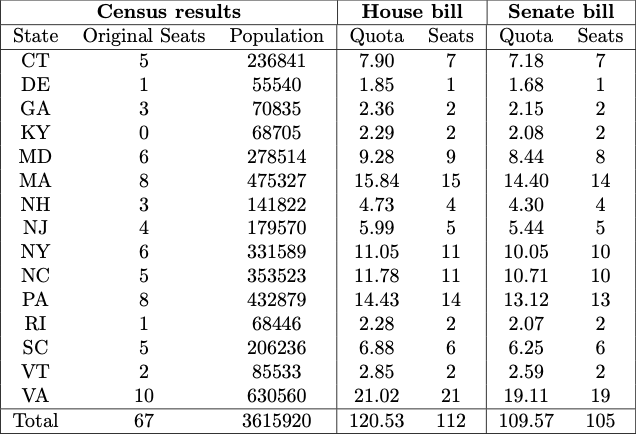

The 1st Census of the United States took place in 1790. The results

were as follows:

The House was aiming for 30,000 people per representative with 112

total representatives. The Senate was aiming for 33,000 people per

representative with only 105 total representatives.

The Math

The formula to calculate the quota for each state is very simple.

Quota = Population/Divisor

Jefferson’s Method

The method advocated by Thomas Jefferson involved these steps:

Calculate the quotas for each state.

Round all the quotas down. If that is the right total number of

seats, you are done, otherwise do step 3.

Adjust the divisor and repeat steps 1 & 2 until you get the

right total number of seats in the House of Representatives.

The Debate

There was a lot of debate about whether the House or Senate

apportionment bill was better.

Several states argued that in the House bill, Virginia got too many

seats. Here’s why. In the House bill, there were supposed to be 112

seats in Congress. Since the population of the US was 3,615,920, the

size of a congressional district should be

d = 3, 615, 920 people/112

representatives = 32, 285 people per representative.

This is called the standard divisor which you always

get by dividing the who population by the number of seats.

Virginia’s Quota Violation

Using the standard divisor, Virginia has a standard

quota of Quota = Population/Divisor = 630, 560/32, 285 = 19.531.

But since the method used to calculate the quota did not use the

standard quota, Virginia ended up with 21 seats.

Virginia would get more seats than its standard quota rounded up.

When a state gets more seats than its standard quota rounded up or less

than its standard quota rounded down, that is called a quota

violation.

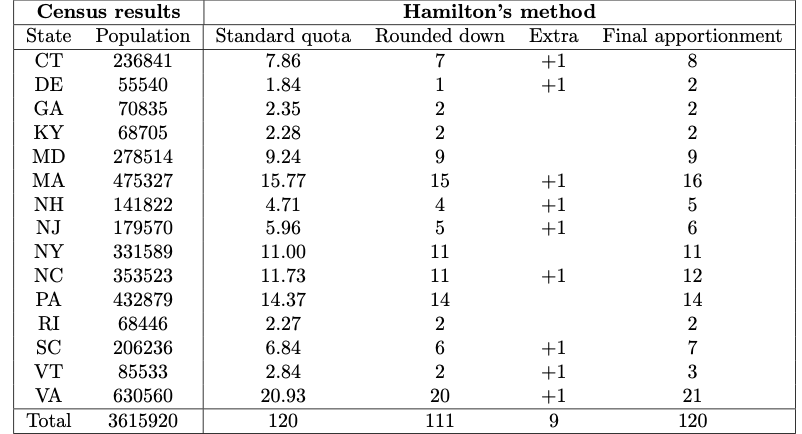

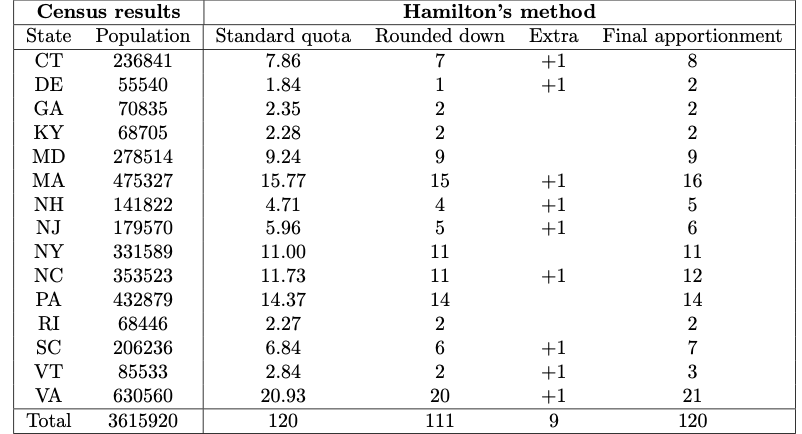

Hamilton’s Method

Alexander Hamilton thought it was unfair for Virginia to get more

seats than it deserved. He persuaded Congress to pass a bill using a

different method which is now called Hamilton’s

method.

Calculate the standard quotas using the standard

divisor.

Every state gets at least their standard quota rounded

down.

If there are seats left over, give one to each of the states with

the highest decimal part in their quotas until they are used

up.

The Apportionment Act of 1792

Using Hamilton’s method, Congress agreed on 120 representatives so

the standard divisor would be 3, 615, 920/120 = 30, 132.67 people per

representative.

The First Veto

Thomas Jefferson argued that it would be more fair to adjust the

divisor (typically by making it a little smaller) so that the quotas can

all be rounded down. He was worried that states would argue about who

would get the extra seats. George Washington agreed with Thomas

Jefferson and so he vetoed the Apportionment Act.

Instead, the original Senate bill for a House of Representatives with

105 seats apportioned using Jefferson’s method was settled on.

Jefferson’s method was used from 1790 through 1832.

Washington’s Explanation

Gentlemen of the House of Representatives:

I have maturely considered the act passed by the two Houses entitled

“An act for an apportionment of Representatives among the several States

according to the first enumeration,” and I return it to your House,

wherein it originated, with the following objections:

First. The Constitution has prescribed that Representatives shall be

apportioned among the several States according to their respective

numbers, and there is no one proportion or divisor which, applied to the

respective numbers of the States, will yield the number and allotment of

Representatives proposed by the bill.

Second. The Constitution has also provided that the number of

Representatives shall not exceed I for every 30,000, which restriction

is by the context and by fair and obvious construction to be applied to

the separate and respective numbers of the States; and the bill has

allotted to eight of the States more than I for every 30,000.

GO WASHINGTON.

Webster’s Method

In 1842, Congress used Webster’s method to apportion

the seats of Congress. Webster’s method and a competing method proposed

by John Quincy Adams (called Adam’s Method) are very

similar to Jefferson’s method. The only difference is in how you round

the quotas:

In Jefferson’s method, you always round quotas down (but never

less than one).

In Adam’s method, you always round quotas up.

In Webster’s method, you round the normal way.

Hamilton’s Method Returns

In 1852 Congress passed a law making Hamilton’s method the “Official”

method for apportionment. But weird things can happen with Hamilton’s

method. This was first discovered in 1882.

Congress was trying to pick how big the House of Representative

should be.

With 299 seats, Alabama got 8 seats.

With 300 seats, Alabama only got 7 seats.

Adding a seat would cause Alabama to lose a seat.

Congress decided to avoid the issue in 1882 by choosing 325 seats

(where both Hamilton’s method and Webster’s methods gave the same

apportionments).

Alabama Paradox

It is really weird that adding more seats to Congress can cause a

state to lose a seat! This is called the Alabama

paradox.

The same paradox happened again in 1901. That year the Census Bureau

presented Congress with tables showing what the apportionment would be

if the size of the House of Representatives was any number between 350

and 400. For most options Maine got 4 seats, but if the House had 357,

382, 386, or 389 seats, then Maine would only get 3 seats. Something

similar happened where Colorado would get either 3 seats or 2 depending

on the size of Congress. Coincidentally, the proposed size of the House

of Representatives was going to be 357 which would have negatively

affected both Maine and Colorado.

After a huge debate, Congress chose to use Webster’s method.

Other Paradoxes

There are other weird things that can happen with Hamilton’s

method.

Population Paradox. If the populations of the

states change, then a state that grows might lose a seat to a state that

doesn’t grow (or even shrinks)!

New States Paradox. When new states get added to

the country, even if you increase the number of representatives by

enough to cover the new states, the apportionment of representatives to

the old states might change.