| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Aug 26 | TP01, C2 | Introduction to Python & Thonny |

| Wed, Aug 28 | TP02 | Variables & functions |

| Thu, Aug 29 | TP02 | Statements versus expressions |

| Fri, Aug 30 | C2.6 | Binary & floating-point numbers |

Today we introduced Python and the Thonny IDE (Integrated Development Environment).

We learned how to use the Python Shell and how to write Python scripts. We also covered the following:

+, -,

*, /)int, float,

and str)We talked about how operators follow an order of

operations, and if operators have the same level of precedence,

then they are computed left to right. We also talked about how some

operators don’t work for all types. For example, the +

operator concatenates strings, but the * operator is not

defined for strings.

We finished by writing a script to calculate the volume of a sphere.

# A script to calculate the volume of a sphere.

PI = 3.14159

radius = 4

volume = 4 / 3 * PI * radius ** 3

print("The volume of the sphere is:", volume)We talked about which variable names are allowed. Some words cannot be used as a variable names because they are special Python keywords. There are currently 35 keywords in Python 3.10 (which is the version we are using), and we’ll cover most of them in this course. Other rules for naming variables include:

_.It is recommended to only use lower case letters only in most

variable names (except when you want to indicate that the variable is

constant and won’t ever change, in which case ALL_CAPS is

recommended). If a variable name has multiple words, then separate the

words with an underscore character, like: surface_area.

We also introduced some new functions including input(),

and the type conversion functions int(),

float(), and str().

We finished by talking about how to import functions

from modules. We imported the math module

which contains functions familiar math functions like

sin(), cos(), and sqrt(). You can

use the command dir(math) to list all of functions in the

math module.

How could you tell if the sine and cosine function expect the input in degrees or radians? Test your idea in the shell and see what the default is.

What happens if you type math.sin without an

input?

What happens if you enter help(math.sin)?

What does the degrees() function do?

Write a program to calculate the roots of a quadratic polynomial using the quadratic formula

Today we talked about some of the errors that came up in the quadratic formula programs from yesterday. There are three categories of errors in Python.

Keep in mind that syntax refers to the structure and grammar of a program, while semantics refers to its meaning. Computers are very picky about syntax, but they are completely oblivious to semantics.

The first error we looked at was this incorrect line of code:

(x1 = (-b + math.sqrt(b ** 2 - 4 * a * c)) / (2 * a))To explain this error, we talked about the difference between statements and expressions in Python.

Every expression is a statement, but not vice versa. In Python, every valid line of code is a statement.

# Example statements

import math

a = 5.0

b = 3 + a

print("Hello")

# Example expressions

1+1

5.0

(-b + math.sqrt(b ** 2 - 4 * a * c)) / (2 * a)Notice that statements can include expressions. A special kind of statement is an assignment statement where you assign a value to a variable. Every assignment statement has the form:

variable_name = # some expressionYou can always wrap an expression in parentheses, and it will still

be an expression with the same value. But, the reason the line of code

(x1 = (-b + math.sqrt(b ** 2 - 4 * a * c)) / (2 * a)) is

not correct is that an assignment statement is not an expression, and

cannot be wrapped in parentheses.

Some functions return values and some functions don’t. For example,

math.sqrt(4) returns the value 2.0, so it can

be used as an expression. But the function print("Hello")

does not return a value. The input() function returns a

string with whatever input the user types. So you can use an assignment

statement like

a = input("Enter a value for the coefficient a. ")to prompt the user to input a number for a. Be careful,

the value that you get will be a string. You have convert it to a number

using the int() or float() functions before

you can use it in a formula.

Today we talked about binary numbers and how Python stores integers and floating point numbers under the hood. We started by talking about how to convert base-2 numbers to base-10. We did the following examples.

Convert to base-10.

Convert to base-10.

Convert to base-10.

Convert to base-10.

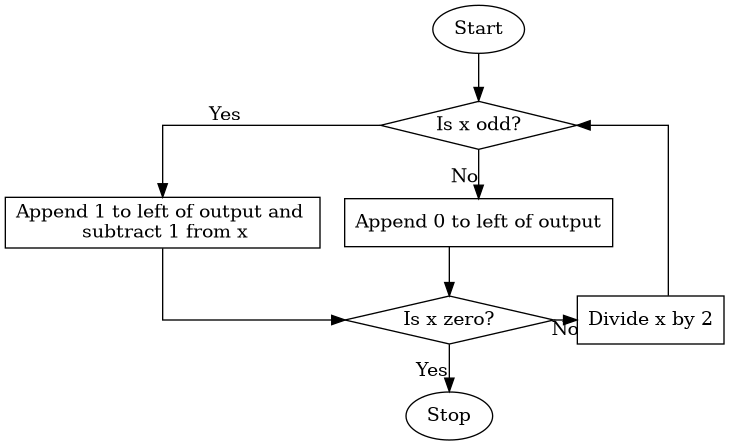

After that we talked about how to convert base-10 integers to base-2. That is a little bit harder, so we introduced the algorithm below which can be described using a flow chart:

Use the algorithm above to convert 35 to base-2.

Use the algorithm above to convert 13 to base-2.

After we introduced binary numbers, we talked about bits and how many integers can be stored using bits. One example is that the maximum number of rupees (money) you could have in the original Zelda game was 255 because the data was stored using 8 bits. Unlike a lot of programming languages, Python allows arbitrarily large integers. This avoids integer overflow errors, but it can be slower for large integers.

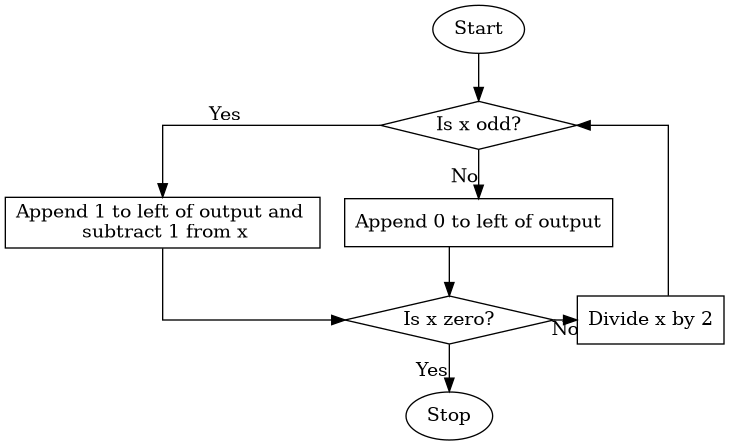

We also talked about how computers store floating point numbers. Most modern programming languages (including Python) store floating point numbers using the IEEE 754 standard.

In the IEEE 754 standard, a 64-bit floating point number has the form where

Compare the output you get when you type 2**1024

versus 2.0**1024 in the Python shell.

Compare the output for 2.0**(-1024) versus

2**(-1070). Notice that you lose precision with small

floating point numbers, but you don’t get an error the way you do with

large floats.

Why do you get an incorrect answer when you enter

0.1+0.1+0.1?

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 2 | Labor Day, no class | |

| Wed, Sep 4 | TP03 | Functions |

| Thu, Sep 5 | TP03 | For-loops |

| Fri, Sep 6 | TP04 | Turtle graphics |

To create your own functions in Python, use the def

keyword to define them:

def hello():

print("Hello!")Every function is a function object. So

function is a type just like int,

float, and str. When you refer to a function

object in Python, there is a difference between the

name of the function (which is hello in

the previous example) and the way you call the function

to get it to run by typing hello(). Here is another

function example.

def print_twice(string): # The first line is called the **header**

print(string) # All of the other lines are called the **body of the function**

print(string) # Notice that all of the lines of the body must be indentedThis function has a parameter which is the variable

called string in the parentheses. We you call this

function, you need to include an argument which is a

value for the parameter.

>>> print_twice("Hello")

Hello

Hello

>>> print_twice(5)

5

5In this example, “Hello” and 5 are arguments. The variable called

string in the function is a parameter. Weirdly, when we

pass the argument 5 to the function, then the parameter called

string stores the value 5 which is an integer not a string!

But that is okay, because Python knows how to print integers.

Functions can have as many parameters as needed. Try to make your own functions to do the following.

Define a function called sum_of_squares that adds up

the squares of two numbers.

Define a function called sphere_volume that

calculates the volume of a sphere.

When you create a function, you should always include a docstring that briefly explains what the functions does. A docstring is a comment that is written using triple quotes instead of the hash symbol. Here is an example.

def circle_area(radius):

"""Returns the area of a circle."""

PI = 3.14159

return PI * radius ** 2The advantage of a docstring over a regular comment is that it can take up multiple lines. Python style guides recommend using docstrings even for one line descriptions of functions, since you might need to add more explanation later.

This last example includes a local variable called PI.

Any variable created in a function body is local, which

means it can only be used inside the function. You won’t have access to

local variables outside the function. Variables defined in a program

that aren’t parameters or defined in the body of a function are

global an can be accessed anywhere in a program.

We finished with a function that calls another function in its body:

def cylinder_volume(radius, height):

"""Returns the volume of a cylinder."""

return circle_area(radius) * heightToday we introduced for-loops. We started with two example functions to demonstrate how they work.

def box(n):

"""Prints an n-by-n square made of * symbols."""

for i in range(n):

print("*" * i)

def print_numbers(n):

"""Print the first n positive numbers."""

for i in range(1,n+1):

print(i)Notice that the range function can accept up to three

arguments (start, stop, and

step). We talked about how Python is **zero-indexed**. For therangefunction, this means that be default it starts counting at zero, so it always stops before the value of thestop`

parameter. We did these exercises.

Write a function to print the first n perfect squares (i.e., 1, 4, 9, 16, etc.)

Write a function to print a triangle with n rows like this:

*

**

***

****Write a function to print an upside down triangle with n rows:

****

***

**

*Write a function to print a hollow n-by-n square, like this example when n is 4:

****

* *

* *

****We finished by talking about accumulator variables in loops. I showed this example.

def sum_of_squares(n):

"""Returns the sum of the first n perfect squares."""

total = 0 # total is an accumulator variable

for i in range(1,n+1):

total += i ** 2

return totalToday we played with turtle graphics

using the turtle module in Python. We started by creating a

turtle object we called fred and then using

fred to draw a square. We ended up creating several

functions using fred to draw different kinds of shapes.

import turtle

fred = turtle.Turtle()

def polygon(side_length, n):

"""Draw a polygon with n sides."""

for i in range(n):

fred.forward(side_length)

fred.left(360 / n)

def circle(radius):

"""Draw a circle."""

side_length = 2 * 3.14159 * radius / 50

polygon(side_length, 50)We finished with some excercises using these funtions.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 9 | TP05 | Conditional statements |

| Wed, Sep 11 | TP05 | Boolean expressions |

| Thu, Sep 12 | ||

| Fri, Sep 13 |

Today we talked about how to implement conditional statements using the keywords if, then, and else in Python. We started with some simple examples.

Body mass index is a quantity used to determine if people are a healthy weight or overweight. The formula for someone’s body mass index is

BMI = (weight / height**2) * 703Anyone with a BMI of 25 or more is considered overweight. Write a program to calculate someone’s BMI and then use an if-then statement to determine if they are overweight.

If someone’s BMI is less than 18.5, they are considered

underweight. Write a function called

weight_category(height, weight) that returns one of three

possible strings: healthy, underweight, or overweight, depending on the

corresponding BMI.

Adapt the program to add a fourth category: obese which is anyone with a BMI greater than or equal to 30.

In order to use an if-statement, we need a special kind of expression

that is either true or false. These are called boolean

expressions. Python has a special type called bool

that has only two possible values, True or

False.

banana7). Your function should return a boolean

value.So far we have introduced the following boolean operators

(==, <, >,

<=, and >=). Another important boolean

operator is != which is True when two

expressions are not equal and False if they are equal.

Another really handy operator is the keyword in which

can test whether one string is inside another.

Which of the following strings are inside

"The quick brown fox"?

"quick""Fox""Tqbf""brown fox""he qu"There was no class since I was out with COVID. I recommended watching part of one of the Harvard CS50 with Python online lectures for more about conditionals and boolean expressions.

I sent out some tips and questions to think about when working on project 2:

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 16 | TP05 | Integer division and modulus |

| Wed, Sep 18 | C11 | While-loops |

| Thu, Sep 19 | C11 | While-loops con’d |

| Fri, Sep 20 | TP05 | Recursion |

Today we talked about the integer division operator

// and the remainder or

modulo operator % in Python. We used them

to do these exercises:

Today is Monday, Sep 16. What day of the week will Oct 16th be (without looking at a calendar)? What about Nov 16?

Write a program to convert any number of minutes into hours and minutes. For example, 100 minutes is 1 hour and 40 minutes. We used this example to introduce f-strings to help print the answer.

def time_conversion(minutes):

hours = minutes // 60

minutes = minutes % 60

print(f"There are {hours} hours and {minutes} minutes.")Improve the program to convert minutes into days, hours, and minutes. For example, 1590 minutes should be 1 day, 2 hours, and 30 minutes.

Write a program to make change using the fewest coins possible for any amount of money less than $1.00. For example, 63¢ could be 2 quarters, 1 dime, and 3 pennies.

Today we introduced while-loops. A while-loop is an alternative to a for-loop that is often useful when you don’t know how many steps you need to repeat. We did the following examples.

Use a while loop to find and print all Fibonacci numbers less than .

Write a while loop to repeat a string until the total length is more than .

Change the following function so that it uses a while-loop instead of a for-loop:

def countdown(n):

"""Count down from an integer n, printing each number. When you get to zero, print 'Go!'"""

for i in range(n, 0, -1):

print(i)

print("Go!") def countdown(n):

"""Count down from an integer n, printing each number. When you get to zero, print 'Go!'"""

while n > 0:

print(n)

n -= 1

print("Go!")Write a function called get_valid_input() that

prompts the user to enter an positive even integer. If the user doesn’t

enter a positive even integer, have the program prompt the user again

until they enter a valid input.

Today we talked about while-loops again. We started with this

example, which improves on the get_valid_input() function

from yesterday and also introduces the idea of a while True

loop.

def get_valid_input():

while True:

n = int(input("Enter a positive even number: "))

if n > 0 and n % 2 == 0:

return n

else:

print("That isn't a positive even number. Try again.")

user_input = get_valid_input()

print("You entered", user_input)After that we implemented the Babylonian algorithm for finding square roots.

def sqrt(a, accuracy = 10 ** (-12)):

"""Uses the Babylonian algorithm to find the square root of a"""

x = a

while abs(x**2 - a) > accuracy:

x = (x + a/x) / 2

return xWhen we wrote this example, we talked about why you should not use

== or != on floating point numbers. We also

introduced the idea of default parameters.

Today we did some more practice with while-loops.

Write a function that uses a while-loop to print all of the numbers from 1 to 100.

Write a while-loop to play a number guessing game. Use the

random.randint(1,10) function by importing the

random library to generate a random integer from 1 to 10.

Then have the user guess the number until they get it right.

After that, we talked about recursive functions which are functions that call themselves. You can use recursive functions to repeat code in much the same way as loops. We did the following examples.

Write a recursive version of the countdown(n)

function.

def countdown(n):

"""Prints the numbers from n down to 1, then prints 'Go!'"""

print(n)

n -= 1

if n > 0:

countdown(n)

else:

print("Go!")Re-write the number guessing game using a recursive function instead of a while-loop.

Challenge. Write a recursive function to print the Fibonacci numbers less than .

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 23 | TP06 | Recursion with return values |

| Wed, Sep 25 | docs | Sequence types |

| Thu, Sep 26 | C10.1 | Lists |

| Fri, Sep 27 | TP09 | Lists |

We looked at some more examples of recursive functions.

Write a function to recursively find the n-th Fibonacci number.

Write a function to recursively print all Fibonacci numbers less than .

Write a factorial(n) function.

We also talked about input validation and we

introduced the isinstance(obj, type) function.

# We used this conditional in class

if not isinstance(n, int):

print("n is not an integer.")

# Here is an alternative that also works

if type(n) != int:

print("n is not an integer.")Today we did more practice with loops and recursion. We reviewed how to find the prime factorization of any integer greater than 1. We spent the class on these exercises.

What are the prime factors of 836?

Write a program to print the prime factors of any integer greater than 1.

After that, we talked about lists in Python. Lists are a type the can store more than one value. We introduced how to define a list using square brackets (including an empty list) and how to create a new list by adding two lists together. We finished with these exercises.

Re-write your prime factors program so that it returns a list of prime factors instead of printing them.

Write a function that prompts a user to enter a list of integers. After each integer the user enters, ask them if they are done or not. Have them enter an upper or lowercase letter Y if the answer is yes. Once the user is done, the function should return the list.

We talked about some of the similarities between lists and strings.

They are both sequence types. So they both have a

length which you can find using the len function. You can

access individual elements in any sequence type by using their

index which is their position in the sequence. The

first element has index 0 and the last has index equal to the length

minus one.

Write a function that prints every other character in a string.

Write a function called is_integer_string(s) that

returns true if s is a string with only the digits 0

through 9 as characters.

Write a function called even_elements(numbers) that

(i) counts the number of even integers in a list and (ii) finds the

index of the first even integer. Have the function print a sentence with

both results.

def even_elements(numbers):

# You'll need two accumulator variables for this function.

# One to count the even elements, and

# another to save the index of the first even element when you find it.If you don’t care about the indices, then there is an even easier way to loop through every element of the sequence. You can use the following syntax:

example_list = [2,4,6,7,11,14,20]

for n in example_list:

print(n)Use this new style of for-loop to (re)write some of the functions we talked about last time.

Write an even_elements(numbers) function like the

one from yesterday using this style of loop. It would be a good idea to

use

as the index of the first even number if there aren’t any.

Re-write the is_integer_string(s) function using

this style of list. To make this one more interesting, we first created

a function called is_digit_char(c) that returns

True if and only if c is a length 1 string

that consists of one of the ten digits 0 though 9.

Write a function any_divisors(n, divs) that accepts

an integer n and a list of nonzero integers

divs, and returns true if any of the elements of

divs are a divisor of n.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 30 | TP08 | Strings |

| Wed, Oct 2 | Review | |

| Thu, Oct 3 | ||

| Fri, Oct 4 | Midterm 1 |

We started talking about slices of strings and

lists. We also talked about methods and in particular

the .index() method and the .count() method.

Every sequence type has these two methods.

How would you slice the string

s = "The quick brown fox" to get the word

"quick"?

Write a function that counts how often each vowel (a, e, i, o, u)

occurs in a string and prints the results. It helps to use the

.lower() method for strings which returns a new string that

is all lower case. This let us talk about method

chaining when you call methods like this:

x.method1().method2().

Write a function called split_at(s, char) that

splits a string into a list with two strings. The part before the first

occurrence of char and the part after the first occurrence.

Then re-write this function to split the string at every occurrence of

char and return a list of all sub-strings.

def split_at(s, char):

"""Returns a list of the substrings of s that are separated by char."""

output = []

while char in s:

location = s.index(char)

front = s[0:location]

output += [front]

s = s[location+1:]

return output + [s] # Notice that the last substring in s

# will have to be added at the end.Today we talked about how to trace a program with paper and pencil including a stack diagram for recursive functions. We started with the recursive function from problem 11 on the practice midterm. Then we did these other examples.

Make a table to trace the values of the variables in this loop.

n = 1

for i in range(5):

a = n * i

n = n + aMake a stack diagram to trace this recursive function.

def result(n):

if n == 1:

return 2

else:

return 2 * result(n - 1)Make a stack diagram to trace this recursive function.

def f(k, n):

if k == n:

return k

elif k < n:

return f(k, n - k)

else:

return f(k - n, n)We also talked about how to work with nested lists, including this example:

students = [

["Charlie", 8],

["Lucy", 9],

["Linus", 7],

["Sally": 6]

]

total = 0

count = len(students)

for i in range(count):

total += students[i][1]

print("The average age of the students is ", total / count)| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 7 | C10.3 | Mutability and immutability |

| Wed, Oct 9 | TP07.2 | Reading files |

| Thu, Oct 10 | TP07.2 | Reading files |

| Fri, Oct 11 | Common patterns in loops (map, filter, reduce) |

Today we talked about a major difference between lists and strings. Lists are mutable but strings are immutable. A type in Python is immutable if you can change anything about the value without completely creating a new instance. A type is mutable if you can modify parts of it without completely replacing it. This is one of the trickier things to understand.

# You can change an element in a list but not in a string:

example_list[1] = 'B' # now example_list is [1,'B',True]

example_string[1] = 'I' # this is an error. Strings a are immutable. There are several methods that work for mutable sequence types like

lists, but not for immutable sequences like strings. These include the

.append() method which adds an element to the end of a

list, the .pop() method which removes and element from the

end of a list (and returns its value), and the .sort()

method which changes a list by putting its elements in sorted order.

# Strings are immutable

s = "You can't touch this!"

"""When you create the string "You can't touch this!", it is frozen in computer mememory.

You can reassign the variable s, but that doesn't change the string, it just makes s

point to a different object in memory.

"""

# Lists are mutable. Changes made to a list will be remembered by the computer.

a = [1,2,3]

"""Because of the way lists are stored in memory, two variables can refer to the same list

object. If you make changes to one variable, that will affect the other variable too!

This only happens with mutable types, so watch out for it.

"""

b = a

b.append(4)

print(a) # Weird!!!Try these experiments to get a feeling for how this works.

Let a = [1,2,3] and b = a + [4]. Does

that change a?

What about a = [1,2,3] and b = a

followed by b += [4]? Does that change

a?

Let x = "test" and y = x followed by

y += "s". Does that change x?

Note that adding two lists creates a new list, but the

+= operator does not! We finished with a cautionary example

about the need to avoid unintended side-effects when working with

mutable types:

def average(numbers):

n = len(numbers)

total = 0

for i in range(n):

total += numbers.pop()

return total / n

data = [4, 5, 6]

mean = average(data)

print("The average of", data, "is", mean)Observe that the way we got the numbers to add to the total had the side effect of erasing the data which isn’t what we wanted at all!

Today we talked about how to read the contents of a text file. We

talked about Python file objects which are what you get

when you use the open() function to access the contents of

text file. File objects come with several useful methods for getting the

contents of a file, including:

.read() which returns the contents of a text file as a

string..readlines() which returns a list containing each line

of the file as a separate string.We did the following exercises using a word list contained in this text file: words.txt.

file = open("words.txt")

word_list = file.readlines()

def longest_word(word_list):

biggest_so_far = ""

for word in word_list:

if len(word) > len(biggest_so_far):

biggest_so_far = word

return biggest_so_farWrite a function

count_words(word_list, start_letter) to count how many

words begin with a given letter.

Write a function get_words(word_list, start_letter)

to return a list of all words that begin with a given letter.

It turns out if you write the function get_words first,

then you can use it to easily write the count_words

function without repeating any code by combining get_words

with the len function.

We also looked at the text file grades.txt which contains comma separated values.

The grades for 26 students are stored in a text file grades.txt. Suppose that the final grade in the class is 20% homework, 30% midterms, and 50% final exam. We worked on a program to find the final grade for each student in the class.

We broke the program into three functions:

A function weighted_average(numbers, weights) that

can calculate the weighted average of any list of numbers using any list

of weights.

A function get_student_data(line) that converts a

line from the text file into a list with a students name followed by

their three grades. You can use the string method

.split(",") to separate a string into a list of the

substrings that were separated by commas.

A function final_grades(lines) that computes and

prints the final grades for all of the students.

Here is a version of the final program.

file = open("grades.txt")

lines = file.readlines()

def weighted_average(numbers, weights):

total = 0

for i in range(len(numbers)):

total += numbers[i] * weights[i]

return total

def get_student_data(line):

data = line.split(",")

for i in range(1, len(data)):

data[i] = int(data[i]) # Convert each grade from a str to an int.

"""This is different than what we did in class. Here we are mutating the

entries of the data in place, but that is okay because we don't care about

the local data variable after the function returns."""

return data

def print_final_grades(lines):

for line in lines[1:]:

data = get_student_data(line)

grades = data[1:]

final_grade = weighted_average(grades, [0.2, 0.3, 0.5])

print(f"{data[0]} got a final grade of {final_grade}")

print_final_grades(lines)We’ve spent the last two weeks talking about sequence types, and we’ve seen a lot of examples where we needed to loop through the elements of the sequence with an accumulator variable to accomplish a goal. These goals often fall into one of three patterns:

Mapping the sequence to create a new sequence where every element is replaced using some function.

Filtering which is when we create a new sequence that only contains elements that meet a certain criterion.

The main differences between these patterns are the type of the accumulator variable and what function or expression you use to help perform the accumulation.

| Pattern | Accumulator Variable | Helper Function/Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Map | New list or sequence | How you want to transform each element |

| Filter | New list or sequence | Boolean function or expression to decide which elements to include |

| Reduce | Usually a bool, int, or float | How you want to combine each element with the accumulator variable |

We did the following examples.

In Python, there are built in functions len,

max, min, and sum to perform many

common reduce patterns. One that is not built in is the

prod function which multiplies elements in a sequence of

numbers. Write a prod(numbers) function.

Write a function that converts floating point numbers to strings

in percent form. For example 0.5 should become

"50%". Then map the following list of floats to a list of

percentage strings.

data = [0.4, 0.7, 1.1, 0.01, 0.97]

Write a function called get_firstname that returns

the first name of any one full name. Then use that function to map this

list to a list of first names.

fullnames = [

"Alice Adams",

"Bob Brown",

"Charlie Clark",

"Daisy Davis",

"Edward Evans",

"Fiona Foster",

"George Green",

"Hannah Hill",

"Isaac Ives",

"Jessica Johnson",

"Kevin King",

"Lily Lewis",

"Michael Miller",

"Nora Nelson",

"Oliver Owens",

"Patricia Parker",

"Quinn Quinn",

"Rachel Roberts",

"Samuel Smith",

"Tina Taylor",

"Ulysses Underwood",

"Vanessa Vincent",

"William Wilson",

"Xavier Xander",

"Yolanda Young",

"Zachary Zimmerman"

]long_names that are longer than 10 letters.| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 14 | Fall break, no class | |

| Wed, Oct 16 | More map, filter, & reduce examples | |

| Thu, Oct 17 | TP18.5 | List comprehensions |

| Fri, Oct 18 | TP10 | Dictionaries |

Today we practiced some more examples of mapping, filtering, and reducing lists and other sequence types using loops.

Write a function reverse(s) that reverses a string.

For example, "Hello!" becomes

"!olleH".

Write a function is_palindrome(s) to check if a

string is a palindrome (i.e., spelled the same forward and backwards,

like "yay"). Then use that function to find all of the

palindromes in the file words.txt. Hint, you

will need to remove the \n newline character after you read

the lines of the file. You can do this with the .strip()

method which removes any whitespace characters (spaces, tabs, newlines)

from the beginning and end of strings.

A list comprehension is a fast way to create a new list by applying a map and/or filter pattern to a sequence, all in one line. A list comprehension has the form:

As an option, you can also include a boolean condition that must be satisfied in order for the expressions to be included in the list.

Here are some examples:

# Generate a list of the first 100 perfect squares.

perfect_squares = [n ** 2 for n in range(100)]

# Generate a list of odd perfect squares.

odd_perfect_squares = [n ** 2 for n in range(100) if n % 2 == 1]Exercises:

Write a list comprehension to create a list of the first 20 positive odd numbers.

What is the value of the following Python expression?

[len(x) for x in ['ab', 'xyz', 5, -1.0, '1.23'] if type(x) == str]How could you use the is_palindrome(s) function we

wrote yesterday to get a list of all palindromes in a long

word_list using a list comprehension?

How could you use a get_firstname(s) function that

extracts just the first name from a fullname string to get a list of

first names from a fullname_list?

A partial sum of a list of numbers is a sum of the first

numbers in the list. Write a list comprehension to find all the partial

sums of any list numbers from

until

is the length of numbers.

A dictionary is a special type in Python that holds key/value pairs.

# Example dictionary:

days_by_month = {'Jan': 31, 'Feb': 28, 'Mar': 31, 'Apr': 30, 'May': 31, 'Jun': 30,

'Jul': 31, 'Aug': 31, 'Sep': 30, 'Oct': 31, 'Nov': 30, 'Dec': 31}In the dictionary above, the keys are the months (which are strings). The values are the numbers of days (which are integers). To access the value in a dictionary, you use the key like you would use an index for a list.

print("April has", days_by_month['Apr'], "days.")Why are they called dictionaries? The idea is that you can look things up, just like in a real dictionary. In fact, you could use a Python dictionary to store words and their definitions:

# Using a Python dictionary to store an English dictionary.

word_to_definition = {

"Aardvark": "a nocturnal burrowing mammal that eats ants and termites.",

"Abacus": "a device for making arithmetic calculations by moving beads.",

"Abandon": "to leave completely and finally",

}Things to know about dictionaries.

in to test if a key is in a dictionary,

but not a value.'Feb' in days_by_month # True

30 in days_by_month # FalseYou can loop through keys in a dictionary. Use a loop of the form

for key in dictionary:

Use this to loop through the months in days_by_month and

print out a sentence for each month saying how many days it

has.

Dictionaries are mutable. You can add key/value

pairs, change the values for keys, and remove key/value pairs without

creating a completely new dictionary. Be careful with this! The

following example creates an empty dictionary, and then fills it with

key/value pairs. Try changing the value for Feb from 28 to

29 in days_by_month.

Exercises.

{'name': 'Alice', 'homework': '72, 'midterm': 89, 'final': 66}

{'test': 1, 'test': 2}?

get_keys(d) and

get_values(d) that input any dictionary d and

returns lists of the keys and values of d

respectively.| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 21 | TP10 | Dictionary Comprehensions |

| Wed, Oct 23 | C16 | Iterable types |

| Thu, Oct 24 | TP11 | Tuples |

| Fri, Oct 25 | TP11 | Tuples |

Last time we introduced dictionaries and we finished with this exercise:

get_keys(d) and

get_values(d) that input any dictionary d and

returns lists of the keys and values of d

respectively.We ran out of time before we could discuss the functions, so we started today by talking about how to write those functions using list comprehensions.

get_keys(d):

return [key for key in d]

get_values(d):

return [d[key] for key in d]Instead of using a dictionary, you could store the information for a dictionary in a list of 2 element lists:

days_by_month_list = [['Jan': 31], ['Feb': 28], ['Mar': 31], ['Apr': 30], ['May': 31], ['Jun': 30]],

['Jul': 31], ['Aug': 31], ['Sep': 30], ['Oct': 31], ['Nov': 30], ['Dec': 31]]We came up with the following answers to this question: a. It is

harder to access the values for each key. b. There is no guarantee that

the keys aren’t repeated.

c. For large data sets, checking if an element is in a list is much

slower than checking if a key is in a dictionary.

As an example of the last advantage, we looked at the following problem from the book. A word is reversible, if it is still a valid word when you reverse its letters, e.g., “part” and “trap”. Compare the following two functions that both search through the list of words in words.txt to count how many words are also valid words when they’ve been reversed.

file = open("words.txt")

word_list = [line.strip() for line in file.readlines()]

word_dict = {word: 0 for word in word_list}

def reverse(s):

output = ""

for c in s:

output = c + output

return output

def count_reversible_words1(word_list):

count = 0

for word in word_list:

if reverse(word) in word_list:

count += 1

print("Method 1: There are", count, "reversible words")

def count_reversible_words2(word_dict):

count = 0

for word in word_dict:

if reverse(word) in word_dict:

count += 1

print("Method 2: There are", count, "reversible words")

count_reversible_words2(word_dict)

count_reversible_words1(word_list)The reason why it is easier to check if an element is a key in a dictionary than to check if it is an element of a dictionary has to do with the algorithms. Checking if an element is in a list uses a linear search algorithm which checks every element of the list one at a time until it either finds a match or reaches the end. This can be slow if the list is very long. Checking if a key is present in a dictionary uses a completely different algorithm called a hash table lookup. That has the following steps:

Both steps 2 and 3 in the algorithm are very fast, even if the dictionary is very long.

Notice that we defined word_dict in the program above

using a dictionary comprehension which is an expression

of the form

Dictionary comprehensions work just like list comprehensions. You can also add a boolean condition to restrict which key/value pairs are included if you want:

We finished by doing the following exercise.

combine_to_dict(key_list, value_list)

that returns a dictionary with keys from key_list and

values from value_list.Both lists and dictionaries are examples of iterable types in Python. An iterable is an object that you can loop through using a for-in loop. All sequential types are iterable, but dictionaries are also iterable even though they aren’t sequential. We made the following table to compare lists vs. dictionaries.

| Lists | Dictionaries | |

|---|---|---|

| Accessing Elements |

a[i]

|

d[key]

|

| Adding New Elements |

a.append(new_element)

|

d[new_key] = new_value

|

| Removing Elements |

a.remove(element) or a.pop(i)

|

d.pop(key)

|

| Looping |

for elem in a:

|

for key in d:

|

| Comprehensions |

[exp for var in iterable]

|

{exp1: exp2 for var in iterable}

|

letter_frequency(message) that returns a list showing the

frequencies of each letter in a message string. It would be better for

that function to return a dictionary with keys for each letter. See if

you can re-write letter_frequency(message) to return a

dictionary with a key for each letter and integer values that correspond

to how many copies of each letter appear in the message. Can you write

the function in one line using a dictionary comprehension?We also talked about using a dictionary as a memo in order to memoize a recursive function. We used this example.

# This simple recursive function is very slow when n gets big

def fib1(n):

"""Returns the n-th Fibonacci number."""

if n < 2:

return n

else:

return fib1(n - 1) + fib1(n - 2)

known = {0: 0, 1: 1} # this is a memo variable that stores known Fibonacci numbers

def fib2(n):

"""Returns the n-th Fibonacci number (memoized version)."""

if n in known:

return known[n]

else:

known[n] = fib2(n - 1) + fib2(n - 2)

return known[n]This dramatically improves the performance of this algorithm. Without

memoization, calling fib1(40) took about 20 seconds on my

computer. But calling fib2(40) returns the answer almost

instantaneously.

Some good exercises to get extra practice with dictionaries can be found here:

We did Exercise 01 and the first part of Exercise 02 together as a class.

Today we introduced tuples.

x = 1, 2, 3 into the Python shell. What is

type(x)?A tuple is a sequence type like a list, except tuples are immutable.

You can add tuples, access values at an index, slice, and even multiply

tuples by positive integers, just like lists. But you cannot add new

elements (there’s no .append() method), remove elements (no

.remove() or .pop() methods) or change the

value of an element at an index.

When entering a tuple, you can wrap the comma separated expressions in parentheses.

x = (1, 2, 3)

x = 1, 2, 3 # These two lines do the exact same thing!

y = [(1, 2), (3, 4)]

y = [1, 2, 3, 4] # These do not, since the meaning changes without the parentheses.We talked about the following applications of tuples.

Tuple Assignment. You can assign a tuple of

values (on right of the assignment operator =) to a tuple

of variables (on the left side).

a, b = 1, 2. What are the values of

a and b?a, b, c = 1, 2?a, b = 1, 2, 3?Tuple Return Values. Some algorithms find more than one value and it would be nice if a function implementing an algorithm could return both. You can use a tuple as a return value to do this.

def division_algorithm(n, d):

"""Divides positive integer n by d using repeated subtraction.

Returns the quotient q and the remainder r.

"""

q, r = 0, n # initialize the quotient and remainder

while r >= d:

r -= d

q += 1

return q, rLooping Through Index/Value Pairs in a List.

Sometimes when you loop through a list, you want both the index and

value for each element. There is a function called

enumerate() to get these for any sequence type. We used it

to re-write the argmax function that we have seen

before.

def argmax(number):

"""Return the argument (i.e., index) of the largest element in a list of numbers."""

arg = 0

for i, x in enumerate(numbers):

if x > numbers[arg]:

arg = i

return argLooping Through Key/Value Pairs in a Dictionary.

You can do something similar to simultaneously loops through both the

keys and values of dictionary using the .items()

method.

days_by_month = {'Jan': 31, 'Feb': 28, 'Mar': 31, 'Apr': 30, 'May': 31, 'Jun': 30,

'Jul': 31, 'Aug': 31, 'Sep': 30, 'Oct': 31, 'Nov': 30, 'Dec': 31}

for month, days in days_by_month.items():

print(month, "has", days, "days.")Unlike lists, tuples are hashable, which means that they can be used as keys for dictionaries. This is useful, for example, if you have data on a grid. We used class today to implement a simple 2-player tic-tac-toe game. We used a dictionary to store the tic-tac-toe board data:

board = {

(0,0): " ", (0,1): " ", (0,2): " ",

(1,0): " ", (1,1): " ", (1,2): " ",

(2,0): " ", (2,1): " ", (2,2): " "

}Manually typing in the keys and values in the dictionary above is a bit tedious (and it would be very tedious if the board was bigger!). Write a double loop to fill an empty dictionary with the data above.

Once we have the board data entered, we need a function

print_board() that can print the current state of the

board. It should produce output that looks like:

| | X ---+---+--- | O | ---+---+--- | |

We need a way to prompt the users to pick a row and a column to

make their moves. Write a function called

get_player_move(board, player) that prompts the user with a

sentence like:

X's turn. Enter the position where you want to place an X.

The two players are "X" and "O". Once the

player enters the result, the function should update board.

Since dictionaries are mutable, you can update board

without needing to return anything.

We also talked about how it would be better if the users could enter position numbers on the board instead of typing coordinates:

1 | 2 | 3 ---+---+--- 4 | 5 | 6 ---+---+--- 7 | 8 | 9

To do this we need a function convert_input_to_pair(s)

that converts the player’s input string to an integer and then to a

tuple showing the row & column number.

def convert_input_to_pair(s):

"""Returns the (row, column) tuple corresponding to a user's input."""

n = int(s) - 1

return n // 3, n % 3Use a while True: infinite loop to let two human

players play tic-tac-toe against each other.

There are a lot of other features we might want our tic-tac-toe game to have:

We didn’t have time to include those in our program in class today, but they are things we could add in the future.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 28 | TP18.1 | Sets and set comprehensions |

| Wed, Oct 30 | Search algorithms | |

| Thu, Oct 31 | Sorting | |

| Fri, Nov 1 | C11.13 | Nested loops |

The text file electives.txt from Project 7 contains the elective preferences for 1,000 students. It would be nice to filter this list of words to just the names of each elective, without any repeats. How could we do that?

We implemented option1 in the following exercise:

unique() that reads a list and

outputs a list of its elements without any repeats.Unfortunately, the function we came up with was very slow to find the unique words in the file words.txt. There are other faster options to create a list of all elements without repeats.

Option 2. Loop through the student preferences

and create a dictionary with the electives as keys. Since keys are

unique, it won’t do anything when you try to add a key that is already

there so it should work. Actually, you already did this! Once you have a

dictionary, just use the list() constructor function to

convert it to a list. You’ll get a list of keys (the values won’t be

included).

Option 3. A dictionary is not the only type to

store values using a hash table to quickly look up elements. Another

Python type is called a set. Sets are like

dictionaries, except sets only have keys, no values. You can convert a

list (or any other iterable type) to a set using the set()

constructor function.

You can also use curly braces to create a set like this:

example_set = {"a", "b", 1, 2}You can tell that this is a set and not a dictionary because it does not colons to separate keys from values. Finally, you can also create set comprehensions in Python, just like list and dictionary comprehensions.

powers_of_2_mod_7 = {2 ** k % 7 for k in range(100)}

print(powers_of_2_mod_7){2 ** k % 7 for k in range(100)} and

[2 ** k % 7 for k in range(100)]?

Last time we introduced the set type in Python. Like

other types in Python, sets have a constructor function

called set(). We reviewed some of the constructor functions

we’ve seen like:

int() list()

float() tuple()

str() set()We can use these constructors to write a very simple version of the

unique() function from last time!

def unique(lst): return list(set(lst))

# Notice that you can define a function all on one line if it is really simple!Recall that sets are not subscriptable which means

you can’t access elements of a set s using

s[i] or s[key] like you can for sequence types

or dictionaries. That is because the order in which elements appear in a

set does not matter. For lists however, order matters a lot, and

sometimes it is helpful if the elements are sorted in increasing or

decreasing order.

One advantage of having a sorted list is that it is much faster to check whether an element is in a sorted list. We compared the following two search algorithms:

Binary search can be much faster than linear search. Suppose that a list has length . The time complexity of linear search is which means that the number of steps to run the algorithm is roughly proportional to . That means that if a list is twice as long, the linear search will typically also take twice as long.

Each step in a binary search cuts the length of the list by half. So the total number of steps is proportional to the logarithm of . In computer science we use to mean the base-2 logarithm of . Recall that a base-2 logarithm outputs the power of 2 needed to equal . So for example:

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

We say that binary search has a time complexity of . That means if we double the length of the list, it only takes one extra step to search for a target element. That is much faster! The disadvantage is that binary search only works if the list is already sorted.

Python has built in functions for sorting lists. There are actually

two. One is a function called sorted() that will sort any

iterable type. The other is a .sort() method that sorts

lists in place. That only works with lists because they are mutable.

sorted() function

|

.sort() method

|

|---|---|

| Works for any iterable type | Only works for lists |

| Returns a new list | Returns nothing (sorts in place) |

| Slightly slower | Slightly faster |

Consider the list a below which contains 20 random

numbers. Use the sorted function to create a new sorted

list with the same numbers.

import random

# Create a random list of 20 numbers from 0 to 999.

a = [random.randint(0,999) for k in range(20)]Try to use the .sort() method to sort a

above. What happens when you enter

print(a.sort())?

Try sorted("Hello?") and

"Hello?".sort().

Consider the list of words in words.txt

(see below). Use the function sorted() to sort the words

based on how long they are. Hint: you can do this if you create a list

of pairs with the length of the word followed by the word, e.g.,

(3, "cat").

file = open("words.txt")

word_list = [line.strip() for line in file]Brandon asked if there is a way to sort the pairs in reverse order so

that the longest words come first. Gyabaah pointed out that you can use

the optional argument reverse = True in the function

sorted:

sorted_pairs = sorted(pairs_list, reverse = True)

print(sorted_pairs)Today we did several examples of nested loops.

Create a list of all 52 playing cards in the form rank of

suit. For example, your list should include the

"Jack of Hearts" and the "Two of Clubs" as

well as all the other valid combinations.

suits = ['Hearts', 'Diamonds', 'Clubs', 'Spades']

ranks = ['Two', 'Three', 'Four', 'Five', 'Six', 'Seven',

'Eight', 'Nine', 'Ten', 'Jack', 'Queen', 'King', 'Ace']Consider the following registration data for 26 students at one school.

registration_data = [

{'name': 'Alice Adams', 'classes': ['Engl 490', 'Span 330', 'Phys 260', 'Engl 450', 'Math 260']},

{'name': 'Bob Brown', 'classes': ['Biol 450', 'Govt 330', 'Fren 301', 'Germ 101', 'Phys 450']},

{'name': 'Charlie Clark', 'classes': ['Span 490', 'Span 201', 'Germ 260', 'Hist 301', 'Govt 301']},

{'name': 'Daisy Davis', 'classes': ['Govt 201', 'Span 201', 'Hist 260', 'Math 201', 'Chem 101']},

{'name': 'Edward Evans', 'classes': ['Biol 450', 'Fren 450', 'Econ 102', 'Fren 260', 'Fren 330']},

{'name': 'Fiona Foster', 'classes': ['Hist 330', 'Hist 490', 'Chem 101', 'Germ 490', 'Econ 102']},

{'name': 'George Green', 'classes': ['Span 330', 'Hist 260', 'Chem 301', 'Govt 490', 'Govt 102']},

{'name': 'Hannah Hill', 'classes': ['Biol 490', 'Fren 301', 'Engl 260', 'Engl 301', 'Germ 450']},

{'name': 'Isaac Ives', 'classes': ['Span 330', 'Econ 201', 'Fren 330', 'Biol 450', 'Math 260']},

{'name': 'Jessica Johnson', 'classes': ['Engl 201', 'Econ 102', 'Span 101', 'Govt 330', 'Chem 490']},

{'name': 'Kevin King', 'classes': ['Biol 330', 'Span 260', 'Biol 260', 'Germ 301', 'Math 102']},

{'name': 'Lily Lewis', 'classes': ['Span 301', 'Biol 102', 'Math 330', 'Fren 450', 'Engl 101']},

{'name': 'Michael Miller', 'classes': ['Biol 450', 'Fren 102', 'Fren 201', 'Phys 102', 'Math 102']},

{'name': 'Nora Nelson', 'classes': ['Math 260', 'Fren 101', 'Biol 101', 'Engl 301', 'Germ 260']},

{'name': 'Oliver Owens', 'classes': ['Econ 260', 'Fren 450', 'Biol 260', 'Engl 490', 'Germ 330']},

{'name': 'Patricia Parker', 'classes': ['Phys 101', 'Fren 201', 'Hist 201', 'Germ 330', 'Germ 102']},

{'name': 'Quinn Quinn', 'classes': ['Biol 301', 'Econ 260', 'Biol 101', 'Biol 201', 'Span 101']},

{'name': 'Rachel Roberts', 'classes': ['Biol 450', 'Econ 301', 'Chem 330', 'Germ 260', 'Span 490']},

{'name': 'Samuel Smith', 'classes': ['Hist 260', 'Econ 101', 'Germ 301', 'Govt 301', 'Math 450']},

{'name': 'Tina Taylor', 'classes': ['Govt 450', 'Hist 101', 'Span 201', 'Fren 330', 'Hist 201']},

{'name': 'Ulysses Underwood', 'classes': ['Engl 201', 'Phys 101', 'Engl 101', 'Econ 260', 'Chem 260']},

{'name': 'Vanessa Vincent', 'classes': ['Econ 201', 'Span 101', 'Engl 201', 'Math 260', 'Phys 301']},

{'name': 'William Wilson', 'classes': ['Math 490', 'Math 201', 'Biol 102', 'Germ 260', 'Germ 102']},

{'name': 'Xavier Xander', 'classes': ['Germ 301', 'Govt 101', 'Govt 102', 'Chem 490', 'Hist 102']},

{'name': 'Yolanda Young', 'classes': ['Hist 301', 'Chem 102', 'Govt 330', 'Chem 101', 'Econ 330']},

{'name': 'Zachary Zimmerman', 'classes': ['Biol 330', 'Chem 330', 'Hist 201', 'Phys 490', 'Chem 260']}

] Create a set object with all of the courses these students have registered for.

Create a dictionary object that counts how many students have signed up for each course.

Which students signed up for Span 201?

Which courses have the most students signed up?

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 4 | C9.2 | Program structure |

| Wed, Nov 6 | C9.3 | Function structure & incremental development |

| Thu, Nov 7 | C13.3 | Writing to a file |

| Fri, Nov 8 | C13.3 | Writing to a file - con’d |

Up to now, we haven’t worried much about how we structure our programs. A simple recommended layout for a Python program is the following:

Docstring. Start with a docstring that includes your name (as the author of the program) along with a brief description of what the program does.

Imports (if any). If you need to import any modules, the import statements go right after the docstring, near the top of the file.

Constants (if any). Put any constants next. Note: try to use as few constants as possible, and avoid using any non-constant global variables if you can.

Function Definitions. These will usually be the biggest part of any program.

Main Function. Any code that you want to execute

automatically when you run your program should be put into a function

called main(). It is your choice whether to put the

main() function at the top or bottom of your program, but

you always call the main() function at the very end of the

program.

We constructed an example Python program called

dictionary_tools.py in class.

"""

Dictionary tools.

Author: Brian Lins

This program contains some useful functions for working with dictionaries.

"""

import math

def map_values(d, f):

"""Applies a function f to every value in d and returns a new dictionary."""

return {key: f(value) for key, value in d.items()}

def key_with_max_value(d):

"""Returns the key with the largest value in d."""

best_key, best_value = None, None

# I got a little confused in class trying to figure out the best way to proceed here.

# You need an initial value for the best_key and best_value. Here is one approach.

for key, value in d.items():

if best_key == None or best_value < value:

best_key, best_value = key, value

return best_key

def main():

example_dict = {"A": 1, "B": 2, "C": 3}

print(map_values(example_dict, math.exp))

print(key_with_max_value(example_dict))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main() Notice the last two lines in the program. In Python there is weird

recommended way to call the main() function:

# You can call the main function this way:

main()

# But this is the recommended way to call main:

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()This recommendation has to do with the structure of more complicated Python programs. Python programs can import other Python programs as modules to build more complex programs. When you import a module, you typically only want to import functions from the module. You usually don’t want any code in the module to automatically run.

Python has a special variable called __name__ that is

set when the program starts. If the program is running as a

script (i.e., it is the program that you are running),

then __name__ is automatically assigned the value

"__main__". Otherwise, if the program is being imported as

a module, then __name__ is set to the name

of the module.

Create two .py files. Call one

test_module.py and the other test_script.py.

In each file, include the following line:

print(__name__)In the test_script.py file also add a line to

import test_module. Now run

test_script.py.

What is the type of the __name__ variable?

One reason Python has weird variable names like __name__

and __main__ with double underscores (called

dunders for short) is so that they won’t conflict with

user-defined variable names. In big programs it can be a real problem if

one part of the program has a variable name that conflicts with another

part.

Another example of a dunder variable is __doc__. Every

function has a __doc__ variable which is equal to that

function’s docstring. This is one reason why you should get in the habit

of writing a clear docstring to explain what each function does.

What happens if you use an inline comment like the example below instead of a docstring?

def example_function():

# This is an example function.

return "Hi!"What is the value of example_function.__doc__?

Last time we talked about the structure of programs. Today we talked about the structure of functions. We reviewed some terminology that we’ve talked about before like local variables, parameters, calling, and arguments. Then we talked about the philosophy of functions.

A function should do exactly what it says it will do in its docstring. You should be able to use a function and trust that it will produced the correct output every time, without looking at how it works. In programming, we think of a function as a black box, which means we can use it reliably without knowing what is inside.

Here are somethings to keep in mind when writing functions.

Use Parameters Not Global Variables. Don’t pass information into functions using global variables, especially if those global variables might change. All of the information a function needs should be included in the list of parameters. The one exception is if you have global constants.

Avoid Unintentional Side Effects. A side effect is when a function does more than just finding its return value. A pure function is one with no side effects, it just returns a value at the end. An impure function might change the values of a mutable parameter (like a list or dictionary) in addition to calculating a return value. It can be hard to debug impure functions. One nice thing about Python is that it won’t let you change the values of immutable global variables from inside a function, unless you use a special keyword. Keep in mind that a print statement inside a function is impure, since printing output on the computer screen is a side effect! That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it, but be sure to explicitly describe any intentional side effects of a function when you write the docstring.

Here are some examples.

What is wrong with the caesar_shift function below?

How could it be improved?

text = "the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog."

def caesar_shift(n):

"""Shift all the letters in text by n places, wrapping back around after z."""

output = ""

for char in text:

if "a" <= char <= "z":

old_position = ord(char) - ord("a")

new_position = (old_position + n) % 26

new_letter = chr(new_position + ord("a"))

output += new_letter

else:

output += char

return outputLast time we wrote a program called

dictionary_tools.py which had a function

key_with_max_value. We could use that function to write a

top_keys(d, n) function that returns the n

keys in a dictionary d.

def top_keys(d, n):

"""

Returns a list with the n keys of a dictionary d that have the largest values.

"""

output = []

for _ in range(n):

# Repeat the following step n times:

# remove the key with the largest value from d and add that key to output

best_key = key_with_max_value(d)

d.pop(best_key)

output.append(best_key)

return output Check that this function works. Try it on a dictionary like

example_dict = {"A": 1, "B": 9, "C": 2, "D": 8, "E": 3, "F": 7}What is wrong with this top_keys function?

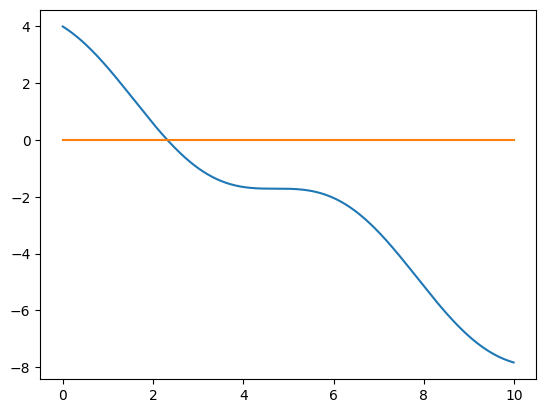

We finished by talking about incremental design where a programming task is broken into small manageable steps that can be tackled one at a time. We used incremental design to start implementing the following function:

def find_root(f, a, b):

"""Find the root of an increasing or decreasing function f on an interval between a and b."""

# Step 1 - Find the midpoint of a and b.

m = (a + b) / 2

# Step 2 - Check if the root is left or right of the midpoint.

# Step 3 - Update the endpoints and midpoint of the interval.

# Step 4 - Repeat.

# Step 5 - Figure out a good stopping point if you never find the exact root.

return mAs you fill in more steps, you can pause and check if the function still runs and produces the output you expect. You can debug as you go. Don’t hesitate to add print statements in the code if things aren’t working the way you expect. You can also use pencil & paper to try to figure out good ways to do each step.

We started by finishing the root finding function from last time.

Then we talked about how to write to files from Python. When you open a

Python file, the default option is the open the file

read-only which means you cannot change the file’s

contents. It is possible to re-write the contents of a file if you open

it with the optional "w" argument.

Try the following short Python program:

file = open("example.txt", "w")

file.write("Hello!")

file.close()What is contained in the file example.txt? Notice that

when we open files with the optional argument "w", it

allows us to write the the file. Any contents that were previously in

the file will get overwritten.

Notice that if you use the .write() method multiple

times, it does not add the contents on separate lines in the file. You

have to add a newline character \n at the end of the string

you are writing to get a line break. Write a program to print the

contents of this list: `fruit_list = [“Apple”, “Banana”, “Orange”,

“Lemon”] each on a separate line of the file.

If you would like to keep the old contents of a file and just add

on to them, use "a" as the optional argument when you open.

Try closing the file after adding the fruit from the

fruit_list. Then open the file again and this time add

"Grapes" without overwriting the other fruit in the

file.

You can run into trouble if you forget to close a file object in

Python because of the way the computer operating system handles files

that are not closed. It is recommended to use a special

with keyword whenever you open a file in Python:

with open("example.txt", "w") as file:

file.write("Hello!")This code does the exact same thing as the code in exercise 1, but

this way you won’t have to remember to close the file at the end. The

with keyword takes care of that automatically. We will

always use this approach to open files from now on.

The file average_temps.txt contains data on the average high temperature in Farmville, VA for each day of the year. Save the file on your computer and open the data:

with open("average_temps.txt") as file:

data = [line.strip().split(";") for line in file.readlines()]Now that you have the data, write a program that converts the

data from Fahrenheit to Celsius and then saves the data in new file

called celsius_temps.txt. Recall that the formula to

convert Fahrenheit to Celsius is

Write a program that uses the same data to find the average high

temperature (in Fahrenheit) for each of the twelve months and then

writes that information into a file

monthly_temps.txt.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 11 | TP14 | Introduction to classes |

| Wed, Nov 13 | TP15 | Magic methods |

| Thu, Nov 14 | TP15 | Static versus instance methods |

| Fri, Nov 15 | TP15 | Calling magic methods |

Up to now, when we need a data type to represent complicated data, we’ve either used a list or a dictionary (or maybe a string, tuple, or set). But sometimes it would be nice if we could create our own custom data types. Object-oriented programming is a programming paradigm that allows users to create new data types that include both data and functions for working with that data. Python uses class objects to implement object oriented programming.

Before we construct our first Python class, let’s look at some data. The files sunrise.tsv and sunset.tsv contain tables stored in tab separated value format with the times of sunrise and sunset for every day of the year (2024) here at Hampden-Sydney (source: https://gml.noaa.gov/grad/solcalc/). Here is a link if you want to preview the sunset data.

If we want to write a program to work with sunset and sunrise times, we could convert all of this data to integers (minutes). That would work, but then we would also need to write some helper functions. For example, we would need:

"1:30" to an

integer number of minutes."1:30".We might also want functions to find the difference and sum of two different times:

We could create a function called time_difference()

that would find the difference between two time strings like

"1:30" and "2:45" and return

"1:15".

We could create a function called add_times() that

would add times together.

There are other functions we could probably think of too. Since all of these functions are only for working with one special type of data, a better approach would be to create a Python class. A class is a custom data type that you can define in Python. Usually we use a capitalized word as the name of a class, and then define the class using code like the following:

class Time:

def __init__(self, hours, minutes):

self.hours = hours

self.minutes = minutesThis is a very basic class. The special function called

__init__ inside the class is the constructor

function which tells Python how to construct an

instance of the Time class. To call this

special function, all we need to do is this:

x = Time(5,40)Now the variable x is an instance of the

Time class. We also say that x is a

Time object. When we initialized this

Time object, we passed two arguments, hours and minutes.

Then we told Python to set the values of self.hours and

self.minutes to those two numbers. Now the object

x has two attributes, .hours

and .minutes. We can access the values of these attributes

using dot-notation:

print(x.hours)

print(x.minutes)So far this class is very basic. Let’s add some functionality by

adding a method to convert a Time object

to minutes.

class Time:

def __init__(self, hours, minutes):

self.hours = hours

self.minutes = minutes

def to_minutes(self):

return 60 * self.hours + self.minutesNow when we initialize a Time object, it will have a

.to_minutes() method that we can use to convert it to an

integer. Things to know about objects:

Objects are mutable. Try changing the value of the hours or minutes of x.

Classes are a way to create new types. What happens when you try

to find type(x)?

Classes are a way to organize new data types and the functions that are commonly used on them.

Here are some exercises.

What happens when you try to print a Time object?

Could you write a function called print_time(time_object)

that would do a better job?

Re-write the print_time() function as a method of

the Time class.

Write a function called time_from_minutes(mins) that

converts a number of minutes to a Time object.

We introduced magic methods in Python which are special methods with double underscore names that tell Python how to do common things you might want to do with objects like how to convert them to strings or add them together. We looked at these three example magic methods.

| Magic Method | Purpose |

|---|---|

__str__

|

Tells Python how to convert the objects into strings. |

__add__

|

Tells Python how to add objects with the + operator.

|

__lt__

|

Tells Python how to decide if object1 < object2.

|

We implemented each of these methods for our Time class.

Then we tried to import the file time.py into another

program. This didn’t work and I was a stumped. Luckily Gyabaah pointed

out that Python has a built in time library that overrode

my custom time.py module. So I renamed time.py

to my_time.py and we were good to go.

We finished by reading a tab-separated file with the sunset data and converting each sunset to a time object.

Suppose we create a class called Length that constructs Length

objects with two attributes: a value that is a number and units that are

strings like "inches", "feet",

"yards", "miles", "meters",

etc.

Suppose we want to create a method for this class called

convert_to() as shown below.

class Length:

def __init__(self, value, units):

self.value = value

self.units = units

def convert_to(self, new_units):

conversion_factor = {("inches", "feet"): 1/12, ("feet", "inches"): 12}

self.value *= conversion_factor[self.units, new_units]

self.units = new_unitsHow would we call this method for a class object

x = Length(9, "inches")?

convert_to(x, "feet")"feet".convert_to(x)x.convert_to("feet") <– This is the

best way to call the method.Length.convert_to("feet")Length.convert_to(x, "feet") <– But

this also works!Any method that has the special variable self as its

first parameter is called an instance method and you

should call these method with the following syntax:

The object called object_name gets passed into

the function called method_name as

self. But this also works (and is equivalent):

x.convert_to()? Why do you get

an error message saying it is missing a positional argument? Why does

x.convert_to(x, "feet") say it takes 2 positional arguments

but 3 were given?It is also possible to write methods that don’t input the special

self variable. A method that doesn’t input

self is called a static method. Static

methods are very common in some languages, but seem to be less common in

Python. But sometimes it is helpful to avoid name collisions if a

function that goes with a class is included as a static method instead

of being a standalone function.

class Time:

def __init__(self, hours, minutes):

self.hours = hours

self.minutes = minutes

# This is an instance method:

def to_minutes(self):

return 60 * self.hours + self.minutes

# This is a static method:

def from_minutes(mins):

return Time(mins // 60, mins % 60)To call a static method like from_minutes(), you use the

name of the class followed by the method name:

from_minutes()

above to convert 75 minutes to a Time object?Just like any other functions in Python, methods can be pure or impure. It is very common for instance methods to not return any value, but instead mutate the object in place.

convert_to from the Length class? Try rewriting the method

the other three ways.| Mutate in place | Return new object | |

|---|---|---|

| Instance method | ? | ? |

| Static method | ? | ? |

We started today by reviewing how to call methods. Suppose that we use our Length class from yesterday and define a length object as follows:

x = Length(9, "inches")x.convert_to()? Why do you get

an error message saying it is missing a positional argument? Why does

x.convert_to(x, "feet") say it takes 2 positional arguments

but 3 were given?We talked about the error messages you get, and how you need to

understand that the the object that owns the instance method is what

gets passed as the self variable.

Then we talked about how magic methods often break the pattern for

calling methods. For example, to call the __init__ method

you could try:

__init__(object_name, other

arguments)

but that typically won’t work since the object you are trying to

construction doesn’t exist yet so it doesn’t make sense to try to use

object_name yet.

Instead, you call the __init__ method using a special

expression:

We talked about how other magic methods like __str__ and

__add__ also have special ways called them. For example you

can call the __str__ method using the special builtin

str() function and you call the __add__ method

using the + operator. The object on the left side of

+ gets passed to __add__(self, other) as

self and the object on the right side becomes

other.

We finished with the following in-class exercise.

Consider the rational numbers class below. Define functions to

add and multiply rational numbers. Also define a __str__

method and a method called reduce(self) that mutates a

Rational object by dividing its numerator and denominator by their

greatest common divisor (you can use the math.gcd function

from the math library).

import math

class Rational:

def __init__(self, num, denom):

self.num = num

self.denom = denom

# Add your own code to define these functions

def __str__(self):

def __add__(self, other):

def __mul__(self, other):

def reduce(self):

"""This should mutate a Rational object in place so that

its numerator and denominator are in simplest form.

"""One feature that it would be nice to have is if you could add a Rational object to an integer object:

>>> Rational(1, 2) + 5How could you adjust your __add__ method to allow

this?

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 18 | TP16 | Type conversion and casting |

| Wed, Nov 20 | Sequence and iterator types | |

| Thu, Nov 21 | Review | |

| Fri, Nov 22 | Midterm 2 |

Last time we created a rational numbers class, but it had some limitations.

You could only add two rationals or a rational plus an integer, but not an integer plus a rational.

What about adding floats?

It would be nice if we could input rational numbers other ways: (i) integers are rational, (ii) what about strings like “4/5”?

What about multiplying by integers or floats?

What if you want to convert a Rational class object to a float?

As we discussed solutions to these problems, we saw some cool things you can do in Python.

You can define the __radd__ method by just setting

it equal to __add__. This is because a function name is a