| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Aug 26 | 1.2 | Data tables, variables, and individuals |

| Wed, Aug 28 | 2.1.3 | Histograms & skew |

| Fri, Aug 30 | 2.1.5 | Boxplots |

Today we covered data tables, individuals, and variables. We also talked about the difference between categorical and quantitative variables.

In the data table in the example above, who or what are the individuals? What are the variables and which are quantitative and which are categorical?

If we want to compare states to see which are safer, why is it better to compare the rates instead of the total fatalities?

What is wrong with this student’s answer to the previous question?

Rates are better because they are more precise and easier to understand.

I like this incorrect answer because it is a perfect example of bullshit. This student doesn’t know the answer so they are trying to write something that sounds good and earns partial credit. Try to avoid writing bullshit. If you catch yourself writing B.S. on one of my quizzes or tests, then you can be sure that you a missing a really simple idea and you should see if you can figure out what it is.

We talked about how to summarize quantitative data. We started by reviewing the mean and median. We saw how to find the average in Excel, and we talked about how to find the position of the median in a long list of numbers (assuming they are sorted).

Then we used the class data we collected last time to introduce histograms and stem-and-leaf plots (also known as stemplots). We also talked about how to tell if data is skewed left or skewed right. One important concept is that the median is not affected by skew, but the average is pulled in the direction of the skew, so the average will be bigger than the median when the data is skewed right.

Until recently, Excel did not have an easy way to make histograms, but Google Sheets does. If you need to make a histogram, I recommend using Google Sheets or this histogram plotter tool.

Which is greater, the mean or the median household income?

Can you think of a distribution that is skewed left?

Why isn’t this bar graph from the book a histogram?

We finished with this in-class workshop.

We introduced the five number summary and box-and-whisker plots (boxplots). We also talked about the interquartile range (IQR) and how to use the rule to determine if data is an outlier.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 2 | Labor Day, no class | |

| Wed, Sep 4 | 2.1.4 | Standard deviation |

| Fri, Sep 6 | 4.1 | Normal distribution |

Today we talked about robust statistics such as the

median and IQR that are not affected by outliers and skew. We also

introduced the standard deviation. We did one example

of a standard deviation calculation by hand, but you won’t ever have to

do that again in this class. Instead, we just use software to find

standard deviation for us. We looked at how to find standard deviation

in Excel using the =stdev() function.

We finished by looking at some examples of histograms that have a shape that looks roughly like a bell. This is a very common pattern in nature that is called the normal distribution.

The normal distribution is a mathematical model for data with a histogram that is shaped like a bell. The model has the following features:

The normal distribution is a theoretical model that doesn’t have to perfectly match the data to be useful. We use Greek letters and for the theoretical mean and standard deviation of the normal distribution to distinguish them from the sample mean and standard deviation of our data which probably won’t follow the theoretical model perfectly.

We talked about z-values and the 68-95-99.7 rule.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 9 | 4.1.5 | 68-95-99.7 rule |

| Wed, Sep 11 | 4.1.4 | Normal distribution computations |

| Fri, Sep 13 | 2.1, 8.1 | Scatterplots and correlation |

We reviewed some of the exercise from the workshop last Friday. Then we introduced how to find percentages on a normal distribution for locations that aren’t exactly 1, 2, or 3 standard deviations away from the mean. I strongly recommend downloading the Probability Distributions app (android version, iOS version) for your phone. We did the following examples.

SAT verbal scores are roughly normally distributed with mean μ = 500, and σ = 100. Estimate the percentile of a student with a 560 verbal score.

What percent of years will Farmville get between 40 and 50 inches of rain?

How much rain would Farmville get in a top 10% year?

Estimate the percent of men who are between 6 feet and 6’5” tall.

How tall are men in the 75-th percentile?

There was no class since I was out with COVID. Instead, there was this workshop to complete on your own.

Workshop: Normal distributions 2

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 16 | 8.2 | Least squares regression introduction |

| Wed, Sep 18 | 8.2 | Least squares regression practice |

| Fri, Sep 20 | 1.3 | Sampling: populations and samples |

We introduced scatterplots and correlation coefficients with these examples:

Important concept: correlation does not change if you change the units or apply a simple linear transformation to the axes. Correlation just measures the strength of the linear trend in the scatterplot.

We finished by talking about explanatory and response variables and how correlation doesn’t mean causation!

We talked about least squares regression. The least squares regression line has these features:

You won’t have to calculate the correlation or the standard deviations and , but you might have to use them to find the formula for a regression line.

We looked at these examples:

Keep in mind that regression lines have two important applications.

After the quiz, we talked about the coefficient of determination which represents the percent of the variability in the -values that follow the tend, the remaining is the percent of the varibility that is above and below the trend line.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 23 | 1.3 | Bias versus random error |

| Wed, Sep 25 | Review | |

| Fri, Sep 27 | Midterm 1 |

We talked about the difference between samples and populations. The central problem of statistics is to use sample statistics to answer questions about population parameters.

We looked at an example of sampling from the Gettysburg address, and we talked about the central problem of statistics: How can you answer questions about the population using samples?

The reason this is hard is because sample statistics usually don’t match the true population parameter. There are two reasons why:

We looked at this case study:

You can avoid/reduce random error by choosing a large sample.

Large samples don’t reduce bias.

The only sure way to avoid bias is a simple random sample.

We started with this workshop (just the front page).

Then we talked about the review problems for the midterm on Friday.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Sep 30 | 1.4 | Randomized controlled experiments |

| Wed, Oct 2 | 3.1 | Defining probability |

| Fri, Oct 4 | 3.1 | Multiplication and addition rules |

Recall that correlation is not causation. The only way to prove that one (explanatory) variable is the cause of a response is to use a randomized controlled experiment. We looked at these examples.

A study try to determine whether cellphones cause brain cancer. The researchers interviewed 469 brain cancer patients about their cellphone use between 1994 and 1998. They also interviewed 469 other hospital patients (without brain cancer) who had the same ages, genders, and races as the brain cancer patients.

In 1954, the polio vaccine trials were one of the largest randomized controlled experiments ever conducted. Here were the results.

We talked about why the polio vaccine trials were double blind and what that means.

Do magnetic bracelets work to help with arthritis pain?

We finished by talking about anecdotal evidence.

Today we introduced probability models which always have two parts:

A subset of the sample space is called an event. We already intuitively know lots of probability models, for example we described the following probability models:

Flip a coin.

Roll a six-sided die.

If you roll a six-sided die, what is

The proportion of people in the US with each of the four blood types is shown in the table below.

| Type | O | A | B | AB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.11 | ? |

What is

We talked about the addition and multiplication rules for disjoint and independent events.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 7 | 3.4 | Weighted averages & expected value |

| Wed, Oct 9 | 3.4 | Random variables |

| Fri, Oct 11 | 7.1 | Sampling distributions |

Today we talked about weighted averages. To find a weighted average:

We did an two examples.

Calculate the final grade of a student who gets an 80 quiz average, 72 midterm average, 95 project average, and an 89 on the final exam.

Eleven nursing students graduated from a nursing program. Four students completed the program in 3 years, four took 4 years, two took 5 years, and one student took 6 years to graduate. Express the average time to complete the program as a weighted average.

We also talked about expected value (also known as the theoretical average) which is the weighted average of the outcomes in a probability model, using the probabilities as the weights.

We finished by talking about the Law of Large Numbers which says: when you repeat a random experiment many times, the sample mean tends to get closer to the theoretical average.

A random variable is a probability model where the outcome are numbers. We often use a capital letter like or to represent a random variable. We use the shorthand to represent the expected value of a random variable. Recall that the expected value (also known as the theoretical average) is the weighted average of the possible outcomes weighted by their probabilities.

A probability histogram shows the probability distribution of a random variable. Every probability distribution can be described in terms of the following three things:

In the game roulette there is a wheel with 38 slots. The slots numbered 1 through 36 are split equally between black and red slots. The other two slots are 0 and 00 which are green. When you spin the wheel, you can bet that the ball will land in a specific slot or a specific color. If you bet $1, and the ball lands on the specific number you picked, then you win $36.

Find the expected value of your bet.

Draw a probability histogram for this situation.

Describe the shape of the distribution.

What does the law of large numbers predict will happen if you play many games of roulette?

We also looked at what happens if you bet $1 on a color like black. Then you win $2 if it lands on black. It turns out that the expected value is the same, but the distribution has a different shape (more skewed) and much larger spread ( for betting on a number versus if you bet on black).

We finished by talking about the trade-off between risk () versus expected returns () when investing. We also looked at what happens if you play a lot of games of roulette using this app.

Suppose we are trying to study a large population with mean and standard deviation . If we take a random sample, the sample mean is a random variable and its probability distribution is called the sampling distribution of . Assuming that the population is large and our sample is a simple random sample, the sampling distribution always has the following features:

Sampling Distribution of .

Examples of sampling distributions.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 14 | Fall break, no class | |

| Wed, Oct 16 | 5.1 | Sampling distributions for proportions |

| Fri, Oct 18 | 5.2 | Confidence intervals for a proportion |

We started with this warm-up problem which is a review of the things we talked about last week.

Then we talked about sample proportions which are denoted . In a SRS from a large population, is random with sampling distribution that has the following features.

Sampling Distribution of .

We did the following exercises in class.

In our class, 13 out of 28 students were born in VA. Is a statistic or a parameter? Should you denote it as or ?

Assuming that the true proportion of all HSC students that were born in VA is 50%, describe the sampling distribution for in a random sample of students.

About one third of American households have a pet cat. If you randomly select households, describe the sampling distribution for the proportion that have a pet cat.

According to a 2006 study of 80,000 households, 31.6% have a pet cat. Is 31.6% a statistic or a parameter? Would it be better to use the symbol or to represent it?

Last time we saw that is a random variable with a sampling distribution. We started today with this exercise from the book:

Then we talked about the following simple idea: there is a 95% chance that is within 2 standard deviations of the true population proportion . So if we want to estimate what the true is, we can use a 95% confidence interval:

The confidence interval formula has two parts: a best guess estimate (or point estimate) before the plus/minus symbol, and a margin of error after the symbol. The formula for the margin of error is 2 times the standard error which is an approximation of using instead of .

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 21 | 5.2 | Confidence intervals for a proportion - con’d |

| Wed, Oct 23 | Review | |

| Fri, Oct 25 | Midterm 2 |

Today we talked about confidence intervals for a

population proportion again. We talked about how you can change the

confidence level by adjusting the critical

z-value

.

| Confidence Level | 90% | 95% | 99% | 99.9% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical z-value | 1.645 | 1.96 | 2.576 | 3.291 |

Examples.

In 2004 the General Social Survey found 304 out 977 Americans always felt rushed. Find the margin of error for a 90% confidence interval with this data.

What are we 90% sure is true about the confidence interval we found? Only one of the following is the correct answer. Which is it?

Confidence intervals for proportions are based on some big assumptions.

No Bias. The data must be a simple random sample from the population to avoid bias.

Normality. The sample size must be large enough for to be normally distributed. A rule of thumb (the success-failure condition) is that you should have at least 15 “successes” and 15 “failures” in your data in order to use this kind of confidence interval.

We finished with one more exercise.

We talked about the midterm 2 review in class today. The solutions are online too.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Oct 28 | 5.3 | Hypothesis testing for a proportion |

| Wed, Oct 30 | 6.1 | Inference for a single proportion |

| Fri, Nov 1 | 5.3.3 | Decision errors |

Today we introduced hypothesis testing. This is a tool for answering yes/no questions about a population parameter. You start by considering two possible hypotheses about the parameter of interest.

Here are the steps to do a hypothesis test for a single proportion:

State the hypotheses. These will pretty much always look like

Calculate the test statistic. Using the formula

Find the p-value. The p-value is the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as the sample statistic if the null hypothesis is true.

Explain what it means. A low p-value is evidence that we should reject the null hypotheses. Usually this means that the results are too surprising to be caused by random chance along. A p-value over 5% means we definitely should not reject .

| p-value | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Over 5% | Weak evidence |

| 1% to 5% | Moderate evidence |

| 0.1% to 1% | Strong evidence |

| Under 0.1% | Very strong evidence |

We did two full examples in class. For each example, you should be able to do each of the four steps above to test the hypotheses.

One other example we didn’t have time to finish was this one.

We reviewed the steps for doing a hypothesis test about a population proportion. The we did this example that we ran out of time for last time:

We talked about how the null hypotheses must give a specific value for the parameter of interest so that we can create a null model that we can test. If the sample statistic is far from what we expect, then we can reject the null hypothesis and say that the results are statistically significant. Unlike in English, the word significant does not mean “important” in statistics. It actually means the following.

Logic of Hypothesis Testing. The following are all equivalent:

Notice that all of the items on the list above are statistics jargon except item 5.

We finished with two exercises from the book.

Notice that in 5.16(b), you could make the case that we have prior knowledge based on the reputation of the state of Wisconsin to guess that that percent of people who have drank alcohol in the last year in Wisconsin (which we denoted ) satisfies a one-sided alternative hypothesis: If you don’t know about Wisconsin, then you should definitely use the two-sided alternative hypothesis: The only difference is when you calculate the p-value, you use two tails of the bell curve if you are doing a two-sided p-value. If you aren’t sure, it is always safe to use a two-sided alternative.

When we do a hypothesis test, we need to make sure that the assumptions of a hypothesis test are satisfied. There are two that we need to check:

We looked at whether these two assumptions are satisfied for this example:

Another thing you have to decide when you do a hypothesis test is how strong the evidence needs to be in order to convince you to reject the null hypothesis. Historically people aimed for a significance level of . A p-value smaller than that was usually considered strong enough evidence to reject . Now people often want stronger evidence than that, so you might want to aim for a significance level of . I’m some subjects like physics where things need to be super rigorous they use even lower values for . Unlike the p-value, you pick the significance level before you look at the data.

In the back of your mind, remember there are four possible things that might happen in a null hypothesis.| is true | is true | |

|---|---|---|

| p-value above | Don’t reject | Type II error (false negative) |

| p-value below | Type I error (false positive) | Reject |

If is true, then the significance level that you choose is the probability that you will make a type I error which is when you reject when you shouldn’t. The disadvantage of making really small is that it does increase the chance of a type II error which is when you don’t reject even though you should.

In a criminal trial the prosecution tries to prove that the defendant is “guilty beyond a reasonable doubt”. Think of a type I error as when the jury convicts an innocent defendant. A type II error would be if the jury does not convict someone who is actually guilty.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 4 | 6.2 | Difference of two proportions (hypothesis tests) |

| Wed, Nov 6 | 6.2.3 | Difference of two proportions (confidence intervals) |

| Fri, Nov 8 | 7.1 | Introducing the t-distribution |

Today we talked about two-sample hypothesis tests for proportions. We did two examples in class:

In the 2008 General Social Survey, people were asked to rate their lives as exciting, routine, or dull. 300 out of 610 men in the study said their lives were exciting versus 347 out of 739. Is that strong evidence that there is a difference between the proportions of men and women who find their lives exciting?

In 2012, the Atheist Shoe Company noticed that packages they sent to customers in the USA were never arriving. So they did an experiment. They mailed 89 packages that were clearly labeled with the Atheist brand logo, and they also sent 89 unmarked packages in plain boxes. 9 out of the 89 labeled packages did not arrive on time compared with only 1 out of 89 unlabeled packages. Is that a statistically significant difference? (See this website for more details: Atheist shoes experiment)

In both examples we used the following theory. In a large enough random sample from two populations A and B, the gap between the sample proportions has a sampling distribution with:

From this theory we talked about how to test the following hypotheses:

using the test statistic: where is the pooled proportion:

You do need a big enough sample for the normality assumption to hold, and you need the samples to not be biased. A rule of thumb for the sample size is that you should have at least 5 successes and failures for each group.

If we want to estimate how big the gap between the population proportions and is, then you can use a two-sample confidence interval for proportions:

Because the formulas for two-sample confidence intervals and hypothesis tests are so convoluted, I posted an interactive formula sheet under the software tab of the website. Feel free to use it on the projects when you need to calculate these formulas.

Two sample confidence intervals for proportions are a little less robust than hypothesis tests. It is recommended that you should have at least 10 successes & 10 failures in each group before you put much trust in the interval.

We started with this example:

Then we did a workshop.

We reviewed statistical inference which is the process of using sample statistics to say something about population parameters. There are two main techniques:

We have been focused on inference about proportions of a categorical variable. Today we started talked about how to do inference about a quantitative variable like height. We looked at our class data and saw that the sample mean height is inches. That suggests that maybe Hampden-Sydney students are taller than average for men in the United States. So we made these hypotheses:

To test these, we reviewed what we know about the sampling distribution for , and we tried to find the z-value using the formula Unfortunately, we don’t know the population standard deviation for all HSC students. We only know the sample standard deviation which was inches. If we use that instead of , then we get a t-value: which follows a t-distribution. We talked about how to use the t-distribution app to calculate probabilities on a t-distribution. One weird thing about t-distributions is that they have degrees of freedom (denoted by either df or ). When you do a hypothesis test for one mean or a confidence interval for one mean, We briefly talked about why this is. Then we used the app to find a p-value for our class data and see whether or not we have strong evidence that HSC students are taller on average than other men in the USA. The logic of p-values is exactly the same for a t-test as it is for a hypothesis test with the normal distribution.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 11 | 7.1.4 | One sample t-confidence intervals |

| Wed, Nov 13 | 7.2 | Paired data |

| Fri, Nov 15 | 7.3 | Difference of two means |

A t-distribution confidence interval is a tool to estimate the value of a population mean ():

In order to use this formula, you need to find the critical t-value for the confidence level you want. The easiest way is to look up the value on a table.

We talked about how to use the table to find -values. Then we did the following examples.

Use the class data to make a 95% confidence interval for the average height of all HSC students.

Use the class data to make a 90% confidence interval for the average weight of all HSC students.

We also did this workshop.

t-distribution methods require the following assumptions:

No Bias. Data should be a simple random sample from the population.

Normality. The sampling distribution for should be normal. This tends to be true if the sample size is big. Here is a quick rule of thumb:

One interesting mistake came up in a couple of the Project 1 write-ups. The confidence interval for the difference in survival rates for the two groups of monkeys ranges from 3% lower with calorie restriction to 35% higher. Several people said that because most of the interval is positive, that means we can conclude that calorie restriction probably increases survival rates. That is actually not true! The mathematics that lets us make a confidence interval don’t tell us anything about where the true parameter falls within the interval. So we have to be very careful about using a confidence interval or hypothesis test to say more than what it actually says.

After that, we talked about comparing the averages of two correlated variables. You can use one sample t-distribution methods to do this as long as you focus on the matched pairs differences. The key is to focus on the difference or gap between the variables. For a matched pairs t-test, we always use the following:

| Hypotheses | Test Statistic |

|---|---|

Does the data in this sample of couples getting married provide significant evidence that husbands are older than their wives on average? What is the average age gap? Use a one-sample hypothesis test and confidence interval for the average difference.

Are the necessary assumptions for a t-test and a t-confidence interval satisfied in the previous example?

Do helium filled footballs go farther when you kick them? An article in the Columbus Dispatch from 1993 described the following experiment. One football was filled with helium and another identical football with regular air. Each football was kicked 39 times and the two footballs alternated with each kick. The distances traveled by the balls on each kick is recorded in this spreadsheet: Helium filled footballs.

Does this data provide statistically significant evidence that helium filled footballs go farther when kicked?

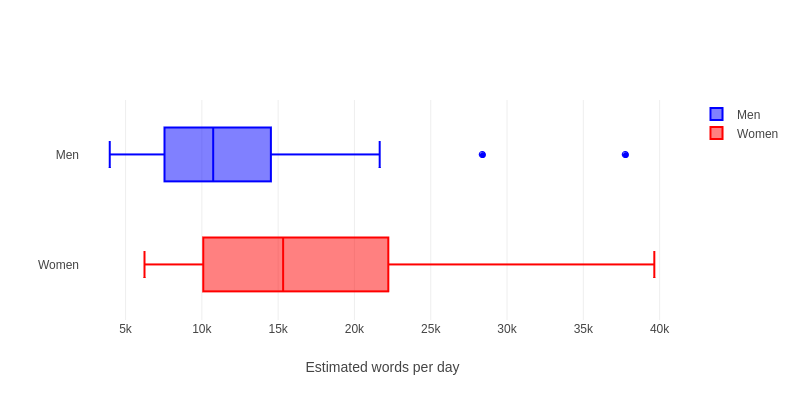

Today we introduced the last two inference formulas from the interactive formula sheet: two sample inference for means. We looked at this example which is from a study where college student volunteers wore a voice recorder that let the researchers estimate how many words each student spoke per day.

We made side-by-side box and whisker plots for the data:

This picture suggests that there might be a difference between men & women, but is it really significant? Or could this just be a random fluke? To find out, we can do a two sample t-test.

| Hypotheses | Test Statistic |

|---|---|

When you do a two sample t-test (or a 2-sample t-confidence interval), there is a complicated formula for the right degrees of freedom. But an easy safe approximation is this: in other words, use the smaller sample size minus 1 as the degrees of freedom.

Here is a quick summary of the numbers we need to calculate the t-value for the example with men & women talking.

| Women | 27 | 16,496.1 | 7,914.3 |

| Men | 20 | 12,866.7 | 8,342.5 |

Cloud Seeding. An experiment done in the 1970’s looked at whether it is possible to spray clouds with a silver iodide solution to increase the amount of rain that falls in an area. On 26 days with promising clouds a plane sprayed the clouds with silver iodide solution and on 26 similar days they didn’t spray. The amount of rainfall (measured in acre-feet) was tracked by radar. Here were the results:

| Seeded | 26 | 16,496.1 | 7,914.3 |

| Control | 26 | 12,866.7 | 8,342.5 |

Is there statistically significant evidence that cloud seeding works to produce more rain?

Use the two sample t-confidence interval to estimate how much more rain cloud seeding would produce on average.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 18 | 7.3 | Difference of two means |

| Wed, Nov 20 | Review | |

| Fri, Nov 22 | Midterm 3 |

Today we started by talking about the assumptions of the two-sample t-methods (both hypothesis tests and confidence intervals).

No Bias. As always, we need good simple random samples to avoid bias.

Normality. The t-distribution methods are based on the normal distribution. If the sample sizes are big enough, then you don’t need to worry to much about normality. Two-sample t-distribution methods are very robust, which means they tend to work well even with data that isn’t quite normal.

We did this example:

In a random sample of students who took the SATs twice found 427

had paid for coaching before their second try and 2733 had not. The

table below shows the average improvements of both groups on their

Verbal SAT scores:

|

Coached |

29 |

59 |

427 |

|

Not |

21 |

52 |

2,733 |

A 2-sample t-test has a t-value of

which has a corresponding p-value of

.

Explain what that means about coaching and the SATs?

Use a 2-sample confidence interval to estimate how much more students would gain with coaching than without.

How are the results of the 2-sample confidence interval different than the 1-sample confidence intervals we could construct for each group?

Today we reviewed for the midterm. We talked about three questions you should ask to decide which inference formula(s) to use:

Choosing the right inference method

Are you estimating a number (confidence interval) or answering a yes/no question about significance (hypothesis test)?

Do you have one sample or two?

Are you interested in percents of a categorical variable

(proportions) or averages of a numerical variable (means)?

We also did some of the midterm 3 review problems in class. We did this additional exercise that was not on the review:

We also reviewed the logic of hypothesis testing Finally, don’t forget to memorize the definition of a p-value!

Definition. A p-value is the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as what happened, if the null hypothesis is true.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Nov 25 | 7.4 | Statistical power |

| Wed, Nov 27 | Thanksgiving break, no class | |

| Fri, Nov 29 | Thanksgiving break, no class |

Recall the difference between type I and II errors.

| Type I error (false positive) | Type II error (false negative) |

|---|---|

| Evidence looks statistically significant, but in reality there is no effect. | Evidence does not look significant, but in reality there is an effect. |

The best way to avoid Type II errors is to use big sample sizes. But how big is big enough? One way to tell is to estimate the margin of error based on plausible guesses about the data you might see.

Definition. A hypothesis test is statistically powerful if the sample size is large enough so that random error probably won’t cause a Type II error. You can tell if test is powerful by estimating the margin of error of a confidence interval with plausible data and making sure it is smaller than the effect size you hope to find.

We did this workshop in class:

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Dec 2 | 6.3 | Chi-squared statistic |

| Wed, Dec 4 | 6.4 | Testing association with chi-squared |

| Fri, Dec 6 | Choosing the right technique | |

| Mon, Dec 9 | Last day, recap & review |

We started by reviewing a two really important concepts: association is not causation and only randomized controlled experiments can prove cause-and-effect. In Project 3 we saw that there is a strong (statistically significant) association between whether states increased speed limits and the percent change in traffic fatalities. The difference was probably not a random fluke, but we can’t conclude that it was definitely the speed limit change that caused the increase in fatalities. That’s because there might be other lurking variables that we haven’t ruled out (maybe some of those states also changed their alcohol laws, or the rules about teenage drivers).

Being able to say that an association is statistically significant is useful, but it is not the same as proving cause-and-effect.

This week we are going to introduce one more inference technique known as the chi-squared test for association. The statistic let’s you measure if an association between two categorical variables is statistically significant. Before we talked about the statistic, we looked at two-way tables. We talked about how to find row and column percentages in a two-way table.

The 2003-04 National Health & Nutrition Exam Survey asked participants how they felt about their weight (options were “underweight”, “about right”, or “overweight”). The results are shown in the two-way table below, broken down by gender.

| Female | Male | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | 116 | 274 | 390 |

| About right | 1175 | 1469 | 2644 |

| Overweight | 1730 | 1112 | 2842 |

| Total | 3021 | 2855 | 5876 |

What percent of women said that they felt overweight?

What percent of overweight people were women?

An association between two categorical variables is statistically significant if there is strong evidence that the association holds in the population, not just in the sample. In a χ² test, you always test the following hypotheses:

To determine whether or not to reject , use a computer to find the statistic for the two-way table. If is true, then the statistic should follow a χ² distribution with degrees of freedom equal to: You can use the χ² distribution app to find the corresponding p-value.

The two-way table above has a chi-squared statistic of . How many degrees of freedom does the table have and what is the corresponding p-value?

Is the association between gender and perceived body weight statistically significant?

A study from the 1990s looked at whether the anti-retroviral drug AZT can help prevent pregnant women with HIV from passing the virus on to their children. The mom’s were randomly assigned to receive either AZT or a placebo, and the results are shown in the two-way table below.

|

HIV-positive baby |

HIV-negative baby |

|

|---|---|---|

|

AZT |

13 |

167 |

|

Placebo |

40 |

143 |

This table has . Is this strong evidence that AZT works better than a placebo?

Today we talked some more about the -test for association. We mentioned that the -distribution has these features:

The assumptions for the -test are:

We did the following example where the -test is inconclusive:

The 2008 General Social Survey asked people if they were “very happy”, “pretty happy”, or “not too happy” with their lives. Here are the results broken down by gender.

|

Female |

Male |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Very Happy |

271 |

328 |

|

Pretty Happy |

513 |

587 |

|

Not Too Happy |

142 |

174 |

This table has . Is there a statistically significant association between the two variables in this two way table? What are the two variables?

Today we talked some more about choosing the right inference techniques in statistics.

Today we went over answers to the review questions for the final exam.