| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 12 | Working with R and Rstudio | |

| Wed, Jan 14 | 1.3 | Sampling principles and strategies |

| Fri, Jan 16 | 1.4 | Experiments |

Today we went over the course syllabus and talked about making R-markdown files in Rstudio. We started the following lab in class, I recommend finishing the second half on your own. I also recommend installing Rstudio on your own laptop (it’s free).

Today we reviewed populations and samples. We started with a famous example of a bad sample.

Then we reviewed population parameters, sample

statistics, and sampling frames. The

difference between a sample statistic and a population parameter is

called the sample error.

There are two sources of sample error:

Bias. Can be caused by a non-representative sample (sample bias) or by measurement errors, non-response, or biased questions (non-sample bias). The only way to avoid sample bias is a simple random sample (SRS) from the whole population.

Random error. This is non-systematic error. It tends to get smaller with larger samples.

To summarize:

We finished with this workshop.

If you find an association between an explanatory variable and a response variable in an observational study, then you can’t say for sure that the explanatory variable is the cause. We say that correlation is not causation because there might be lurking variables that are confounders, that is, they are associated with both the explanatory and response variables and so you can tell what is the true cause.

It turns out that randomized experiments can prove cause and effect because random assignment to treatment groups controls all lurking variables. We also talked about blocking and double-blind experiments.

Example: 1954 polio vaccine trials

Workshop: Experiments

We finished by simulating the results of the polio vaccine trials to see if they might just be a random fluke. We wrote this R code in class:

results = c()

trials <- 1000

for (x in 1:trials) {

simulated.result <- sample(c(0,1), size = 244, replace = TRUE)

percent <- sum(simulated.result) / 244

results <- c(results, percent)

}

hist(results)

sum(results < 0.336) / trials| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 19 | Martin Luther King day - no class | |

| Wed, Jan 21 | 2.1 | Examining numerical data |

| Fri, Jan 23 | 3.2 | Conditional probability |

Today we did a lab about using R to visualize data.

You should be able to open this file in your browser, then hit CTRL-A and CTRL-C to select it and copy it so that you can paste it into Rstudio as an R-markdown document.

We had a little trouble with R-markdown on the lab computers.

Last time we talked about how to visualize data with R. Here are two quick summaries of how to make plots in R:

After that, we started talking about probability. We review some of the basic rules.

The notation means “the probability of B given that A happened”. Two events and are independent if the probability of does not depend on whether or not happens. We did the following examples.

We also talked about tree diagrams (see subsection 3.2.7 from the book) and how to use them to compute probabilities.

Based on a study of women in the United States and Germany, there is an 0.8% chance that a woman in her forties has breast cancer. Mammograms are 90% accurate at detecting breast cancer if someone has it. They are also 93% accurate at not detecting cancer in people who don’t have it. If a woman in her forties tests positive for cancer on a mammogram screening, what is the probability that she actually has breast cancer?

5% of men are color blind, but only 0.25% of women are. Find .

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 26 | Class canceled (snow) | |

| Wed, Jan 28 | 4.1 | Normal distribution |

| Fri, Jan 30 | 3.4 | Random variables |

Class was canceled today because I had a doctor’s appointment. But I

recommended that everyone watch the following video and then complete a

workshop about the R functions pnorm, qnorm,

and rnorm.

Today we talked about random variables and probability distributions. We talked about some example probability distributions:

Flip a coin until you get a tail. Let represent the number of flips needed. (geometric distribution)

About 1 meteorite bigger than 1000 kg hits the Earth every year. The time until the next meteorite hits the Earth has probability density function . (exponential distribution)

We talked about the difference between continuous and discrete probability distributions. Then we introduced expected value.

If is a discrete random variable, then the expected value of is If is a continuous random variable with probability density function , then the expected value of is

We did the following example.

We finished by talking about what we mean when we say something is “expected”.

If you repeat a random experiment many times, then the average outcome tends to get close to the expected value.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 2 | 3.4 | Random variables - con’d |

| Wed, Feb 4 | 4.3 | Binomial distribution |

| Fri, Feb 6 | 5.1 | Point estimates and error |

For a random variable with expected value , the variance of is The standard deviation of (denoted ) is the square root of the variance.

We did these examples in class.

Here is an extra example from Kahn academy that we did not do in class.

Suppose a random variable has the following probability model.

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

0.1 |

0.15 |

0.4 |

0.25 |

0.1 |

Expected value is linear which means that for any two random variables and and any constant , these two properties hold:

Variance is not linear. Instead it has these properties:

A single six-sided die has expected value and standard deviation . What is the mean and standard deviation if you roll two dice and add them?

Binomial distribution. If is the total number of successes in independent trials, each with probability of a success, then has a binomial distribution, denoted for short. This distribution has

We used this binomial distribution plotting tool to compare the distributions if you make these two bets 100 times. In one case we get something that looks roughly like a bell curve, in the other case we get something that is definitely skewed to the right.

pbinom(x, n, p) function in R.Sometimes the assumption that the trials are independent is not justified.

The correct probability distribution to model the example above is called the hypergeometric distribution. As long as the population is much larger than the sample, we typically do not need to worry about the trials not being independent.

We finished by discussing the normal approximation of a binomial distribution. When is large enough so that both and , then is approximately normal with mean and standard deviation .

Suppose that are independent random variables that all have the same probability distribution. If is large, then the total has an approximately normal distribution.

If each has mean and standard deviation , then what is the mean and the standard deviation of the total?

In Dungeons and Dragons, you calculate the damage from a fireball spell by rolling 8 six-sided dice and adding up the results. This has an approximately normal distribution. What is the mean and standard deviation of this distribution. (Recall that the mean and standard deviation of a single six-sided die is and ).

We looked at a graph of the distribution from the previous example to see that it is indeed approximately normal.

When you use a normal approximation to estimate discrete probabilities, it is recommended to use a continuity correction (see Section 4.3.3). To estimate , calculate using the normal approximation (and likewise, to estimate , compute using the normal approximation).

An important special case of the central limit theorem is the normal approximation of the binomial distribution, which has mean and standard deviation .

pbinom(x, n, p) function.We finished by talking about the difference between the distribution of the total versus the distribution of the proportion of patients who are O-negative. The standard deviation of the sample proportion is

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 9 | 5.2 | Confidence intervals for a proportion |

| Wed, Feb 11 | Review | |

| Fri, Feb 13 | Midterm 1 |

Today we talked about confidence intervals for a proportion.

Sampling Distribution for a Sample Proportion. In a SRS of size from a large population, the sample proportion is random, so it has a probability distribution with the following features.

In practice, we usually don’t know the population proportion . Instead we can use the sample proportion to calculate the standard error of :

If the sample size is large enough, then there is a 95% chance that will be within about two standard deviations of . So if we know and we assume that the standard error is close to the standard deviation for , then we can make a confidence interval for the location of the parameter .

Confidence Interval for a Proportion. This works well if the sample size is very large.

You can use the R command qnorm((1 - p) / 2) to find the

critical z-value

()

when you want a specific confidence level

.

After that, we talked about the prop.test() function in

R which can make a confidence interval (among other things).

Notice that the prop.test() confidence interval is not

the same as what we got using the formula above. Instead of using the

formula above, R uses something called a Wilson

score confidence interval with continuity correction. The idea is to

solve for the two points

where

If you add in the continuity correction, this pretty much guarantees

that there is at least a 95% chance (or whatever other confidence level

you want) that the interval contains the true population parameter. The

Wilson method confidence intervals are fairly trustworthy even with

relatively small samples and small numbers of successes/failures.

Today we went over the midterm 1 review problems (the solutions are also available now). We also did some additional practice problems including these.

If you draw a random card from a deck of 52 playing cards, what is the probability that you draw an ace or a heart?

Suppose you need knee surgery. There is an 11% that the surgery fails. There is a 4% chance of getting an infection. And there is a 3% chance of both infection and the surgery failing. What is the probability that the surgery succeeds without infection?

In the Wimbledon tennis tournament, serving players are more likely to win a point. A server has two chances to serve the ball. There is a 59% chance that the first serve is in, and if it is, then the server has a 73% chance of winning the point. If the first serve is out, then they have an 86% of getting the second serve in, and in that case they have a 59% chance of winning the point. But if the second serve is out, then the server automatically loses the point.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 16 | 5.3 | Hypothesis tests for a proportion |

| Wed, Feb 18 | 6.2 | Difference in two proportions |

| Fri, Feb 20 | 6.2 | Difference in two proportions - con’d |

Today we talked about hypothesis testing, specifically testing hypotheses about a population proportion. We looked at three examples.

In the helper versus hinderer student, 14 out of 16 infants chose the helper toy. Could this be a random fluke? To find out we can do a hypothesis test for proportions.

prop.test() function in

this situation?When you do a hypothesis test, typically you choose a significance level α in advance, and then you calculate a p-value. A p-value is the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as the statistic, if the null hypothesis is true: If the p-value is below the significance level, then you should reject the null hypothesis. The following things are all equivalent:

Conversely, if the results are not statistically significant, then we don’t reject the null, and we should be aware that the results might be a random fluke. Be careful, a common misunderstanding is to think that the p-value is . The p-value does not directly tell you the probability that the null hypothesis is true, it only indirectly suggests that the null might not be true.

In another study, researchers presented 100 college students the images of two men (see the link above) and asked them to guess which was named Tim and which was named Bob. It turned out that 67 students guessed that Tim was the man with the goatee.

If someone gets 10 out of 25 guesses about what Zener card someone is looking at, is this strong evidence that they are psychic? Do a hypothesis test to find out.

The null hypothesis in the last example is that the person is not

psychic, so they only have a 1 out of 5 chance of guessing right. Here

is how you test this using the prop.test() function in

R.

prop.test(10, 25, p = 0.2, alternative = "greater")We talked about how to compare two proportions using confidence

intervals and hypothesis testing. We started by talking about how the

prop.test() function in R can accept a vector of successes

and another vector of totals for more than one group. We used this to

analyze the following study.

A 2002 study looked at whether nicotine lozenges could help smokers who want to quit. The subjects were randomly assigned to two treatment groups. One group got a nicotine lozenge to take when they had cravings, while the other group got a placebo lozenge. Of the 459 subjects who got the nicotine lozenge, 82 successfully abstained from smoking, while only 44 out of the 458 subjects in the placebo did.

We created an R-markdown document to answer these questions in class.

After we did that example, I let everyone work on a similar example on their own:

| Rural | Urban/Suburban | |

| Passed | 30 | 52 |

| Failed | 25 | 13 |

| Total | 55 | 65 |

Use R to visualize the results and carry out a hypothesis test to see if background make a significant difference in student pass rates.

We started with this example that we did not have time for last time.

| Male | Female | |

| Passed | 60 | 23 |

| Failed | 29 | 11 |

| Total | 89 | 34 |

After that we talked briefly about the theory behind the two-sample test for proportions.

Theorem. If and are independent random variables that each have a normal distribution, then also has a normal distribution.

If we take two simple random samples from two populations, the two sample proportions and are each approximately normally distributed.

Two-Sample Hypothesis Test for Proportions.

where is the pooled proportion:

Works best if both samples have at least 5 successes & 5 failures.

Two-sample Confidence Interval for Proportions.

Works best if both samples contain at least 10 successes and 10 failures.

We also talked about one-sided confidence intervals,

which you get automatically in R when you set the

alternative option to either "greater" or

"less".

We finished by introducing the chi-squared statistic where is the expected count in row , column (assuming there is no association), and is the observed count in row , column .

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 23 | 6.4 | Chi-squared test for association |

| Wed, Feb 25 | 6.3 | Chi-squared goodness of fit test |

| Fri, Feb 27 | 7.1 | One-sample means with t-distribution |

You can use the chi-squared test for association to see if there is a significant association between two categorical variables. We did this example using R.

We talked about the difference between long tables (also known as tidy tables) where each row represents one individual and each column represents a variable, versus two-way tables (also known as contingency tables) where the rows and columns represent categories for two categorical variables and the numbers in the table are the counts.

You can easily convert a long table stored as a data frame in R to a

two-way table using the table() function. You can transpose

a two-way table (swap the rows & columns) using the function

t().

We also talked about mosaic plots as an alternative to stacked bar graphs for showing the relationship between two categorical variables.

We did this example:

Suppose that a random sample of 100 people in a city are asked if they think the fire department is doing a satisfactory job. Shortly after the survey, there is a large fire in the city. If the same 100 people are asked their opinions again, you might get results like this:

|

Satisfactory |

Unsatisfactory |

|

|

Before |

80 |

20 |

|

After |

72 |

28 |

For this table, with a p-value of 18.5%. Why should you not trust this p-value?

The right way to look at this data is to include each person once. Each individual person has their before opinion and their after opinion recorded, so we could make a two-way table for those two variables:

|

Satisfactory Before |

Unsatisfactory Before |

|

|

Satisfactory After |

70 |

2 |

|

Unsatisfactory After |

10 |

18 |

We ran out of time at the end, but I gave the following handout as extra practice to think about the chi-squared test for association.

Today we introduced the chi-squared goodness of fit test. It is a lot like the chi-squared test for association, except instead of having two categorical variables, you just have one and you are testing to see whether the proportions in each category from the sample match some model for what the population should be.

We started with this question:

We tested the hypotheses:

We started by trying to find a z-value using but since we do not know the correct standard deviation for the population of all HSC students, we need to switch to using t-values:

students <- read.csv("https://bclins.github.io/spring26/math222/Examples/StudentData.csv")

t.test(students$Height, mean = 70)The t-distribution was discovered by William Gossett while he worked for the Guinness brewing company.

Scientists studying the Earth’s atmosphere found amber resin that

formed 95 to 75 million years ago when dinosaurs lived. They measured

the percent of nitrogen trapped in air bubbles in the resin and found

the following results:

c(63.4, 65, 64.4, 63.3, 54.8, 64.5, 60.8, 49.1, 51). Is

this strong evidence that nitrogen levels back then were significantly

different than they are now? Currently nitrogen is 78.1% of the Earth’s

atmosphere.

nitrogen <- c(63.4, 65, 64.4, 63.3, 54.8, 64.5, 60.8, 49.1, 51)

t.test(nitrogen, mu = 78.1)If you have a small sample (), then you should be careful about trusting the t-distribution methods unless you are sure that the population really has a normal distribution.

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 2 | 7.2 | Paired data |

| Wed, Mar 4 | 7.3 | Difference of two means |

| Fri, Mar 6 | 7.4 | Power calculations |

We started by talking about using quantile-quantile plots to check normality.

We talked about how to tell the difference between left-skewed and right-skewed distributions on a qqplot. You can also use a qqplot to tell if a distribution has tails that are too fat to be normal.

After that, we introduced prediction intervals. A 95% t-distribution confidence interval is supposed to contain the population mean, but it does not contain 95% of the individuals, nor does it have a 95% chance to contain a future observation. But you can make an interval that contains 95% of future observations by using a prediction interval.

Prediction Interval for a Quantitative Variable.

Caution: Unlike confidence intervals, these are not robust if the population is not normal, even if the sample size is large!

We used R to find a 95% prediction interval for next year’s rainfall here in Farmville.

rain <- read.csv('http://people.hsc.edu/faculty-staff/blins/StatsExamples/rainfall.csv')

xbar <- mean(rain$total)

s <- sd(rain$total)

N <- 81

tstar <- qt(0.975, df = 80)

upper <- xbar + tstar * sqrt(s^2 + s^2 / N)

lower <- xbar - tstar * sqrt(s^2 + s^2 / N)We introduced the qt() function which is similar to the

qnorm() function, except it is for the t-distribution.

Then we talked about using the t-test with paired data. We started with this data set which shows the size in cubic centimeters of the left hippocampus region of the brain (measured using MRI) of pairs of twins. Each pair of twins had one who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and one who was unaffected by schizophrenia. So we want to know if the size of the hippocampus is significantly different in twins with schizophrenia.

brain = read.csv('https://www.rossmanchance.com/iscam2/data/hippocampus.txt', sep = "\t")Notice the optional argument sep = "\t" which we had to

use since the data file was stored as tab-separated

values, not comma-separated values. Since the twins come in

matched pairs, we test the differences:

t.test(brain$unaffected - brain$affected)Today we worked on the following examples in class:

For two-sample t-tests, we use Welch’s t-test which is a very robust method. It uses the fact that if you sample from two populations with equal means, then the two-sample t-value: will approximately follow a t-distribution (under very mild normality & independence assumptions). The formula for the degrees of freedom is a bit complicated, but R will calculate it for you automatically.

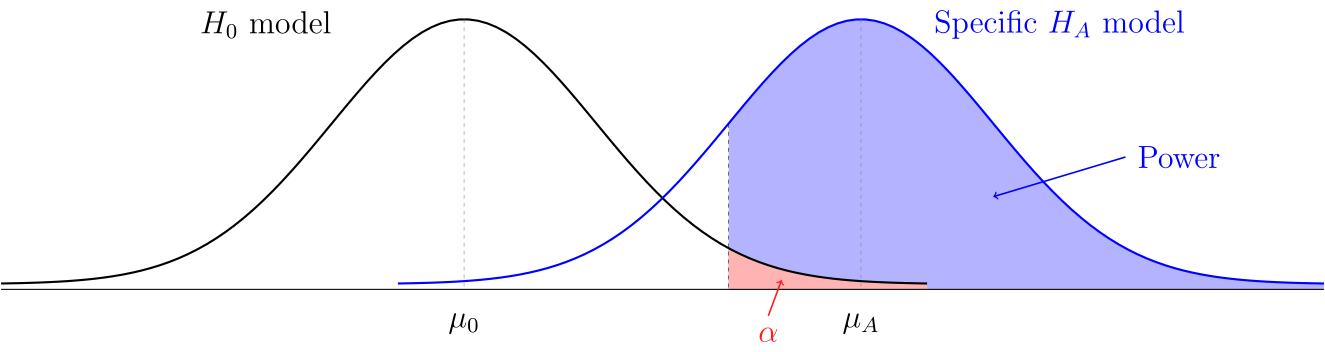

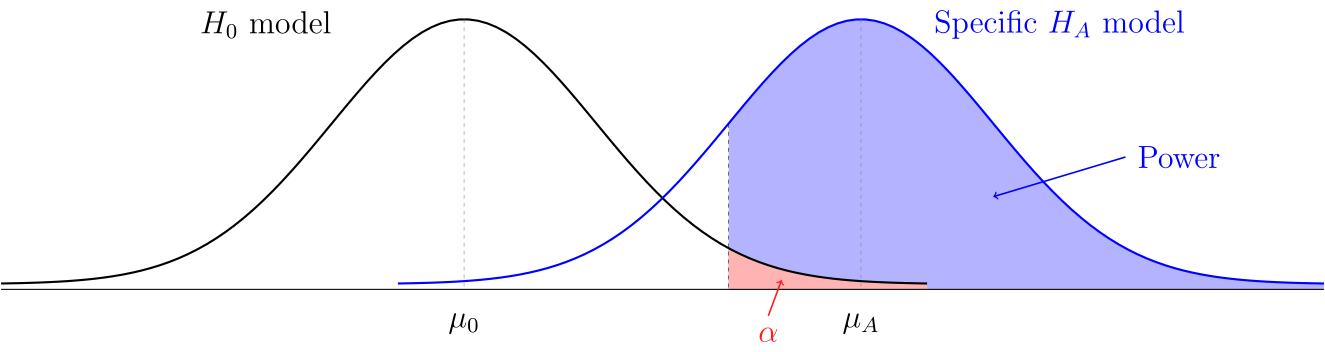

Today we talked about statistical power, significance levels, and Type I versus II errors. Traditionally when people do a hypothesis test, they have a significance level in mind. If the results have a p-value below the significance level, then the researchers can feel justified rejecting the null hypothesis. But there are two potential problems with this type of significance test.

| is true | is true | |

|---|---|---|

| p-value below | Type I error (false positive) | Reject |

| p-value above | Don’t reject | Type II error (false negative) |

If the null hypothesis is true, then the probability of a Type I error is . In order to talk about the probability of a Type II error, we need to make some extra assumptions about the situation, including picking a specific value for the parameter of interest.

Definition. The power of a statistical study is the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis if a specific alternative hypothesis is true.

If you are going to the trouble to design an experiment or observational study, you should probably do a quick power calculation before you start, otherwise you might just be wasting your time. We did these examples:

A 1998 study looked at the herbal supplement Garcinia Cambogia to see if it can help people lose weight. Here is the abstract from the study:

A total of 135 subjects were randomized to either active hydroxycitric acid [The active ingredient in G. Cambogia] (n = 66) or placebo (n = 69); 42 (64%) in the active hydroxycitric acid group and 42 (61%) in the placebo group completed 12 weeks of treatment. Patients in both groups lost a significant amount of weight during the 12-week treatment period; however, between-group weight loss differences were not statistically significant (mean [SD], 3.2 [3.3] kg vs 4.1 [3.9] kg; P = 0.14).

If we wanted to perform a follow-up study to see if G. Cambogia can increase weight loss by at least 1 kg (over a placebo) and if we assume that the standard deviation in weight loss for each group will be around 4 kg, then how large should our groups be in order to get a power of at least 80%? What if we want 90% power?

In the previous example, we were doing a two-sample hypothesis test for means. In that case, the null model says that the difference in sample means should have a normal distribution with mean and standard deviation

We picked an effect size that we would like to detect to be kg. And we talked about why it is safer to round standard deviations up when you are picking plausible values for and in a power calculation, so we picked kg. Then we used the following code to find the power:

n = 100 # We assumed both treatment groups would be same size

sigma_1 = 4

sigma_2 = 4

sigma = sqrt(sigma_1^2/n + sigma_2^2/n)

threshold = qnorm(0.95, mean = 0, sd = sigma)

power = 1 - pnorm(threshold, mean = 1, sd = sigma)

power # The power with n = 100 is only about 54.9%. By testing different sample sizes, you can find an n large enough to get a power of 80% or higher. We didn’t have time for the following example, but it is good practice if you want a power calculation for a 1-sample hypothesis test. For a 1-sample test for means, the null and alternative models will both be normal distributions with standard deviation

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 16 | 7.5 | Comparing many means with ANOVA |

| Wed, Mar 18 | Review | |

| Fri, Mar 20 | Midterm 2 |

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 23 | 7.5 | ANOVA - con’d |

| Wed, Mar 25 | 8.2 | Least squares regression |

| Fri, Mar 27 | 9.1 | Introduction to multiple regression |

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 30 | 9.2 | Model selection |

| Wed, Apr 1 | 9.3 | Checking model conditions |

| Fri, Apr 3 | 9.3 | Checking model conditions - con’d |

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 6 | 9.5 | Introduction to logistic regression |

| Wed, Apr 8 | 9.5 | Logistic regression - con’d |

| Fri, Apr 10 | Hypothesis testing with randomization |

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 13 | Confidence intervals with bootstrapping | |

| Wed, Apr 15 | Review | |

| Fri, Apr 17 | Midterm 3 |

| Day | Section | Topic |

|---|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 20 | Introduction to Bayesian methods | |

| Wed, Apr 22 | Credible intervals for proportions | |

| Fri, Apr 24 | Bayesian inference | |

| Mon, Apr 27 | Last day, recap & review |