| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 12 | Floating point arithmetic |

| Wed, Jan 14 | Relative error, significant digits |

| Fri, Jan 16 | Taylor’s theorem |

We talked about how computers store floating point numbers. Most modern programming languages store floating point numbers using the IEEE 754 standard.

In the IEEE 754 standard, a 64-bit floating point number has the form

where

We talked about how to convert between binary

numbers and decimal numbers.

This system works very well, but it leads to weird outcomes like

0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 = 0.30000000000000004.

When you convert to binary, you get a infinitely repeating binary decimal: So any finite binary representation of will have rounding errors.

We did the following examples in class:

Convert (10110)2 to decimal. (https://youtu.be/a2FpnU9Mm3E)

Convert 35 to binary. (https://youtu.be/gGiEu7QTi68)

What is the 64-bit string that represents the number 35 in the IEEE standard?

What are the largest and smallest 64-bit floating point numbers that can be stored?

In Python, compute 2.0**1024 and

2**1024. Why do you get different results?

In Python, compare 2.0**1024 with

2.0**(-1024) and 2.0**(-1070). What do you

notice?

Today we talked about significant digits. Here is a quick video on how these work.

Rules for Significant Digits.

Next we defined absolute and relative error:

Definition. Let be an approximation of a real number .

The base-10 logarithm of the relative error is approximately the number of significant digits, so you can think of significant digits as a measure of relative error.

Intuitively, addition & subtraction “play nice” with absolute error while multiplication and division “play nice” with relative error. This can lead to problems:

Catastrophic cancellation. When you subtract two numbers of roughly the same size, the relative error can get much worse. For example, both 53.76 and 53.74 have 4 significant digits, but only has 1 significant digit.

Useless precision. If you add two numbers with very different magnitudes, then having a very low relative error in the smaller one will not be useful.

We did these examples in class.

Rounding Error. The worst case relative error from rounding to significant digits is Since 64-bit floating point numbers have up to 53 significant digits, they typically have a relative error of up to . This quantity is known as machine epsilon.

You can sometimes re-write algorithms on a computer to avoid issues with floating point numbers such as overflow/underflow and catastrophic cancellation.

Consider the function . Use Python to compute .

The exact answer to previous question is (accurate to 22 decimal places). Use this to find the relative error in your previous calculation.

A better way to compute is to use a trick to avoid the catastrophic cancellation: Use this new formula to compute . What is the relative error now?

Stirling’s formula is a famous approximation for the factorial function. We approximated Stirling’s formula using the following code.

import math

n = 100

print(float(math.factorial(n)))

f = lambda n: math.sqrt(2 * math.pi * n) * n ** n / math.exp(n)

print(f(n))Our formula worked well until , then we got an overflow error. The problem was that got too big to convert to a floating point number. But you can prevent the overflow error by adjusting the formula slightly to.

n = 143

f = lambda n: math.sqrt(2 * math.pi * n) * (n / math.e) ** n

print(f(n))Today we reviewed Taylor series. We recalled the following important Maclaurin series (which are Taylor series with center ):

We graphed Maclaurin polynomials for and on Desmos to see how they converge with different radii of convergence.

We also use the Maclaurin series for to approximate the integral

Then we did the following workshop in class.

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 19 | Martin Luther King day - no class |

| Wed, Jan 21 | Taylor’s theorem - con’d |

| Fri, Jan 23 | Bounding error |

Today we reviewed some theorems that we will need throughout the course. The first is probably the most important theorem in numerical analysis since it lets us estimate error when using Taylor series approximations.

Taylor’s Theorem. Let be a function that has derivatives in the interval between and . Then there exists a strictly inside the interval from to such that where is the th degree Taylor polynomial for centered at .

A special case of Taylor’s theorem is when . Then you get the Mean Value Theorem (MVT):

Mean Value Theorem. Let be a function that is differentiable in the interval between and . Then there exists a strictly inside the interval from to such that

We did this example:

Then we started this workshop

Last time we started this workshop about using Taylor’s remainder formula and the triangle inequality to find upper bounds for functions. Today we revisited that workshop, but first we talked about the following.

Taylor’s Error Formula. Let be a function that has derivatives in the interval between and . Then where is the maximum value of with between and .

This error formula gives a way to estimate the worst case (absolute) error when you use a Taylor polynomial approximation.

After that we talked about the triangle inequality.

Triangle Inequality. For any numbers and (real or complex),

We talked about how you can use the triangle inequality to find upper bounds for functions. We also talked about tight upper bounds versus upper bounds that are not tight. We did this example.

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Jan 26 | No class (snow day) |

| Wed, Jan 28 | Bisection method |

| Fri, Jan 30 | Newton’s method |

We talked about how to find the roots of a function. Recall that a root (AKA a zero) of a function is an -value where the function hits the -axis. We introduced an algorithm called the bisection method for finding roots of a continuous function that changes sign from positive to negative or negative to positive on an interval . We wrote the following code to implement this algorithm.

def bisection(f, a, b, N):

"""

Applies the bisection method recursively up to N times to estimate a root

of a continuous function f on an interval [a,b].

"""

m = (a + b) / 2

if N == 0 or f(m) == 0:

return m

if (f(a) > 0 and f(m) > 0) or (f(a) < 0 and f(m) < 0):

return bisection(f, m, b, N - 1)

else:

return bisection(f, a, m, N - 1)We tested this algorithm on the function which has a root at .

One feature of the bisection method is that we can easily find the worst case absolute error in our approximation of a root. That is because every time we repeat the algorithm and cut the interval in half, the error reduces by a factor of 2, so that We saw that it takes about 10 iterations to increase the accuracy by 3 decimal places (because ).

Today we covered Newton’s method. This is probably the most important method for finding roots of differentiable functions. The formula is This formula comes from the idea which is to start with a guess for a root and then repeatedly improve your guess by following the tangent line at until it hits the -axis.

Use Newton’s method to find roots of .

How can you use Newton’s method to find ? Hint: use .

Theorem. Let and suppose that has a root . Suppose that there are constants such that and for all . Then when .

Proof. Start with the first degree Taylor polynomial (centered at ) for including the remainder term and the Newton’s method iteration formula:

and

Subtract these two formulas to get a formula that relates with .

Use this to get an upper bound on . □

Corollary. Let . As long as the Newton method iterates stay in , then the absolute error after steps will satisfy

This corollary explains why, if you start with a good guess in Newton’s method, the number of correct decimal places tends to double with each iteration!

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 2 | Secant method |

| Wed, Feb 4 | Fixed point iteration |

| Fri, Feb 6 | Newton’s method with complex numbers |

The secant method is a variation of Newton’s method that uses secant lines instead of tangent lines. The advantage of the secant method is that it doesn’t require calculating a derivative. The disadvantage is that it is a little slower to converge than Newton’s method, but it is still much faster than the bisection method. Here is the formula:

Solve the equation using the secant method. What would make good initial guesses and ?

# This code will do one step of the secant method.

f = lambda x: 2 ** x - 10

a, b = 3, 3.5

a, b = b, b - f(b) * (b - a) / (f(b) - f(a)); print(b)Definition. A sequence converges with order if it converges to and there are constants and such that

Convergence of order is called linear convergence and convergence of order is called quadratic convergence. Newton’s method converges quadratically. It turns out that the secant method converges with order which is the golden ratio!

Newton’s method is a special case of a method known as fixed point iteration. A fixed point of a function is a number such that . A real-valued function has a fixed point on an interval if and only if it intersects the graph on that interval.

Show that has a fixed point in .

Explain why has no fixed points.

Does have any fixed points?

A fixed point is attracting if the recursive sequence defined by converges to for all sufficiently close to . It is repelling if points close to get pushed away from when you apply the function . You can draw a picture of these fixed point iterates by drawing a cobweb diagram.

To make a cobweb diagram, repeat these steps:

Show that the fixed point of is attracting by repeatedly iterating.

Show that has a fixed point, but it is not attracting.

Theorem If has a fixed point and

Proof. Write down the first degree Taylor approximation for centered at . Use it with , to show that if is an upper bound for (near ), then Then as long as is close enough to , the terms inside the parentheses are less than 1 which means that , i.e, is closer to than for every . □

Theorem. If is differentiable at a fixed point and , then for any point sufficiently close to , the fixed point iterates defined by converge to with linear order. If , then the iterates converge to with order where is the first nonzero derivative of at .

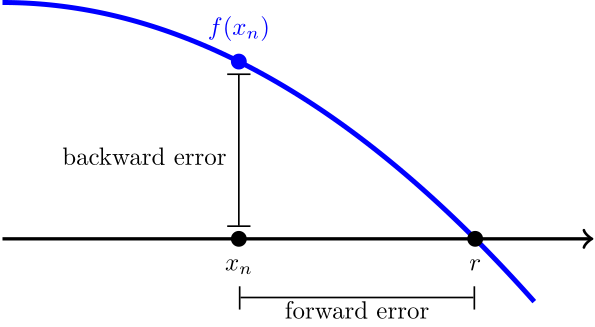

In any root finding method, we have two ways of measuring the error when we compare an approximation with the actual root. The forward error is the distance between the root and the approximation on the -axis. Since we usually don’t know the true value of , it is hard to estimate the forward error. The backward error is just , which is usually easy to calculate.

We used the idea of forward and backward error to automate Newton’s method. The idea is to include an optional tolerance argument. We stop iterating when the backward error is smaller than the tolerance.

def newton(f, Df, x, tolerance = 10 ** (-15)):

"""

Applies Newton's method to a function f with derivative Df and initial guess x.

Stops when |f(x)| < tol.

"""

step = 0

while not abs(f(x)) < tolerance:

x = x - f(x) / Df(x)

step = step + 1

print("Converged in", step, "steps.")

return xWe finished with a cool fact about Newton’s method. It also works for to find complex number roots if you use complex numbers. We did a quick review of complex numbers.

Euler’s formula.

We used the cmath library in Python to do the following

experiments with Newton’s method.

Cube roots of unity. Use Newton’s method to find all 3 roots of .

Euler’s identity. Use Newton’s method to solve .

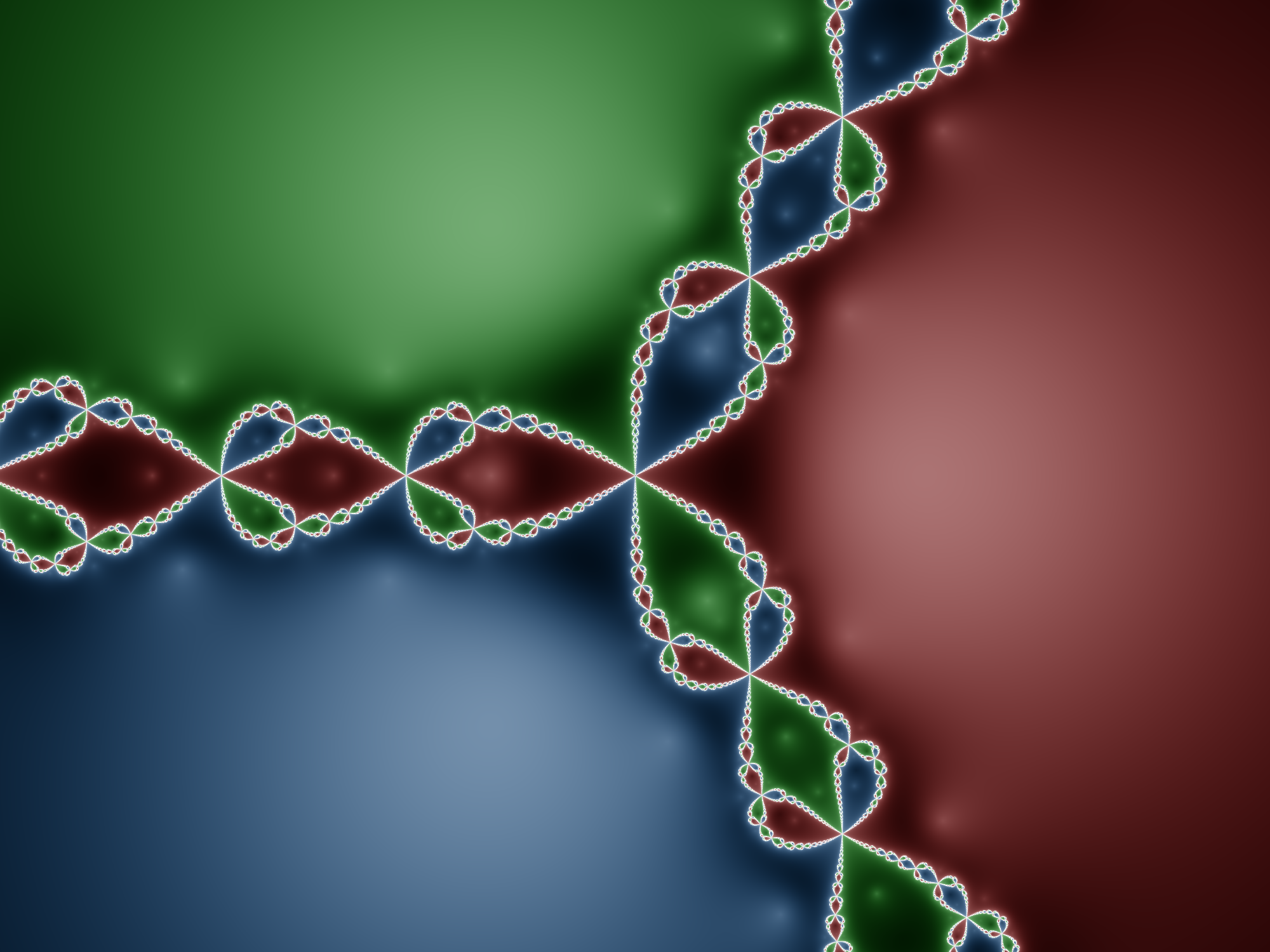

We finished by talking about Newton fractals. When you use Newton’s method on a function with more than one root in the complex plane, the set of points that converge to each root (called the basins of attraction) form fractal patterns.

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 9 | Solving nonlinear systems |

| Wed, Feb 11 | Systems of linear equations |

| Fri, Feb 13 | LU decomposition |

Today we talked about how to solve systems of nonlinear equations with Newton’s method. As a motivating example, we talked about how this could be used in navigation, for example in the LORAN system.

To solve a vector-valued system , you can iterate the formula where is the Jacobian matrix

To program this formula in Python, we’ll need to load the

numpy library. We wrote the following code to solve this

system:

import numpy as np

F = lambda x: np.array([

x[0] * x[1] + x[1]**2 - 1,

x[0]**2 - x[1]**2 - 1

])

J = lambda x: np.array([

[ x[1], x[0] + 2*x[1] ],

[ 2*x[0], -2*x[1] ]

])

x = np.array([1,1])

for i in range(10):

x = x - np.linalg.inv(J(x)) @ F(x) # Use @ not * for matrix multiplication.

print(x)Today we talked about systems of linear equations and linear algebra.

We can represent this question as a system of linear equations. where are the numbers of pennies, nickles, dimes, and quarters respectively. It is convenient to use matrices to simplify these equations: Here we have a matrix equation of the form where , is the unknown vector, and . Then you can solve the problem by row-reducing the augmented matrix

which can be put into echelon form

The variables , and are pivot variables, and the last variable is a free variable. Once you pick values for the free variable(s), you can solve for the pivot variables one at a time using back substitution. We did this using Python:

q = 20

d = 2*q

n = (920 - 9*d - 24*q) / 4

p = 80 - n - d - q

print(p, n, q)

# Only q = 20 makes sense, otherwise either p or n will be negative.After that we reviewed some more concepts and terminology from linear algebra. The most important thing to understand is that you can think of matrix-vector multiplication as a linear combination of the columns of the matrix:

For any matrix :

The column space of is the set of all possible linear combinations of the columns. It is also the range of as a linear transformation from into .

The rank of is the dimension of the column space. It is also the number of pivots, since the pivot columns are a basis for the column space.

The null space of is the set .

The nullity of is the number of free variables which is the same as the dimension of the null space of .

A matrix equation has a solution if and only if is in the column space of . If is in the column space, then there will be either one unique solution if there are no free variables (i.e., the nullity of is zero) or there will be infinitely many solutions if there are free variables.

If

(i.e.,

is a square matrix) and the rank of

is

,

then

is invertible which means that there is a matrix

such that

where

is the identity matrix which is

You can use row-reduction to find the inverse of an invertible matrix by

row reducing the augmented matrix

until you get

.

We did this example in class:

Here is another example that we did not do in class:

Today we talked about LU decomposition. We defined the LU decomposition as follows. The LU decomposition of a matrix is a pair of matrices and such that and is in echelon form and is a lower triangular matrix with 1’s on the main diagonal, 0’s above the main diagonal, and entries in row , column that are equal to the multiple of row that you subtracted from row as you row reduced to .

Compute the LU decomposition of .

Use the LU decomposition to solve .

We also did this workshop.

We finished with one more example.

Here’s another LU decomposition example if you want more practice.

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 16 | Matrix norms and conditioning |

| Wed, Feb 18 | Review |

| Fri, Feb 20 | Midterm 1 |

Notice that even though and are very close, the two solutions are not close at all. When the solutions of a linear system are very sensitive to small changes in , we say that the matrix is ill-conditioned.

Definition. A norm is a function from a vector space to with the following properties:

Intuitively a norm measures the length of a vector. But there are different norms and they measure length in different ways. The three most important norms on the vector space are:

The -norm (also known as the Euclidean norm) is the most commonly used, and it is exactly the formula for the length of a vector using the Pythagorean theorem.

The -norm (also known as the Manhattan norm) is This is the distance you would get if you had to navigate a city where the streets are arranged in a rectangular grid and you can’t take diagonal paths.

The -norm (also known as the Maximum norm) is

These are all special cases of -norms which have the form

We used Desmos to graph the set of vectors in with -norm equal to one, then we could see how those norms change as varies between 1 and .

The set of all matrices in

is a vector space. So it makes sense to talk about the norm of a matrix.

There are many ways to define norms for matrices, but the most important

for us are the induced norms (also known as

operator norms). For a matrix

,

the induced

-norm

is

Two important special cases are

Here is a quick exercise:

For an invertible matrix , the condition number of is . You can use any induced norm to define , but our default will be the induced -norm since it is the only one that is easy to calculate by hand.

If the condition number is large, then the matrix is ill-conditioned. When we try to solve an ill-conditioned linear system, small errors in either or could become large errors in our calculated solution.

Just like with root finding, we can talk about forward and backward error when we try to solve a linear system . The table below defines the absolute and relative forward and backwards errors. In the table, is the exact solution to the system , and is an approximation of .

| Forward Error | Backward Error | |

| Absolute | ||

| Relative |

The following result shows how the condition number lets us estimate the relative forward error using the relative backward error.

Theorem. If is an invertible matrix with condition number , and , then

Proof. By the definition of the induced norm, Since , , so which proves the statement. □

The following is a consequence of this theorem.

Rule of thumb. If the entries of and are both accurate to -significant digits and the condition number of is , then the solution of the linear system will be accurate to significant digits.

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Feb 23 | LU decomposition with pivoting |

| Wed, Feb 25 | Inner-products and orthogonality |

| Fri, Feb 27 | Orthogonal sets & matrices |

Consider the matrix

which has

decomposition

Although

is not ill-conditioned, you have to be careful using row reduction to

solve equations with this matrix because both

and

in the LU-decomposition for

are ill-conditioned.

In Matlab/Octave, you can use the norm(A, inf) function

to find the induced

-norm

of matrix. The function norm(A) computes the induced 2-norm

by default. You can also compute the condition number of a matrix using

cond(A) or cond(A, inf).

Use Octave to find the condition numbers for the matrices , , and above.

B = [0.001 1; 1 1]

L = [1 0; 1000 1]

U = [0.001 1; 0 -999]

cond(B)

cond(L)

cond(U)It is possible to avoid this problem using the method of partial pivoting. The idea is that there is a permutation such that where is a permutation matrix such that has a nice LU-decomposition. The formula is known as the PLU-decomposition or sometimes the LUP-decomposition of . This method fixes two problems:

The algorithm to find the PLU-decomposition is almost the same as the LU decomposition, except you also swap rows so that the largest available entry in a column (in absolute value) becomes the pivot at each step. When you swap two rows of the echelon form matrix , you also have to swap the same rows of and the same rows in the completed columns of (leave the unfinished columns alone). The permutation matrix is the matrix you get by swapping the same rows of the identity matrix as you swapped while you found the PLU decomposition.

In Octave, you can just use the following command to get the PLU-decomposition:

[L, U, P] = lu(A)One nice thing to know about permutation matrices is that they are always invertible and where is the transpose of obtained by converting every row of to a column of .

Show that when you use partial pivoting to row reduce to echelon form, the resulting LU matrices are not ill-conditioned.

Use the PLU-decomposition to solve

Finding the PLU decomposition by hand is tedious, especially if you need to swap more than 2 rows, but here is a good video explanation of how it works:

The inner product of two vectors in is . We proved some important facts about inner products and got some practice with matrix algebra in the following workshop:

In exercise 2 from the workshop last time, we needed the property that . This is a special case of one of the rules for transposes:

Today we talked about two special types of matrices.

A set of vectors is an orthogonal set if every vector in is orthogonal to every other vector in . An orthogonal set where every vector also has length equal to 1 is called an orthonormal set.

Suppose that we have an orthonormal set in that contains two vectors and . If for some angle , then there are only two possible vectors that could be. What are they? Hint: Draw a picture!

If a matrix in has orthonormal columns, then is the n-by-n identity matrix. Use this fact to prove that preserves inner-products. That is for any vectors in .

If has orthonormal columns, then show that preserves lengths, that is, for all in .

A square matrix with orthonormal columns is called an orthogonal matrix.

The first possibility represents all possible rotations of . The second represents all possible reflections. Those are the only length-preserving linear transformations of the plane!

We finished by talking about symmetric matrices. A matrix in is symmetric if .

It turns out that symmetric matrices can only have real eigenvalues and they always have an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors.

Since we had a little extra time, we finished by talking about the conjugate transpose of a complex matrix. For any matrix in , the conjugate transpose is . It combines taking the transpose of with computing the complex conjugate of every entry. Recall that the complex conjugate of a complex number . For matrices with real number entries, and are the same thing. In Matlab/Octave you use an apostrophe to get the conjugate transpose:

A = [1 2i; 3 4i]

A'The conjugate transpose mostly has the same properties as the transpose:

One very important exception is when you work with inner-products of complex vectors. The complex inner-product of in is . But unlike regular inner-products, order matters for complex inner-products because

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 2 | Gram-Schmidt algorithm |

| Wed, Mar 4 | QR decomposition |

| Fri, Mar 6 | Orthogonal projections |

Last week we introduced the orthogonal complement of a set in . You should know that:

The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra. Let be a real -by- matrix. Then

After that we talked about why orthogonal bases are better. We used this example:

Since the two components of the force of gravity are orthogonal, it is easy find the right coefficients for the force of gravity in the angled basis.

Gram-Schmidt Algorithm. Converts a basis into an orthogonal basis for the same subspace.

Start with . Then for each from 2 to , find using these steps:

If you want an orthonormal basis, then just normalize by dividing each by its length.

Apply Gram-Schmidt to , (https://youtu.be/Rz3O6hJ9xZQ)

Apply Gram-Schmidt to , , . (https://youtu.be/Rz3O6hJ9xZQ?t=350)

We started with these two warm-up problems.

Find the orthogonal projection of onto the line spanned by . Then find two orthogonal vectors and such that lies in the span of and .

Find the orthogonal projection of onto the plane spanned by and .

In order to calculate the second orthogonal projection, we used the following formula:

Orthogonal Projection onto a Subspace. If is a subspace of with an orthogonal basis , then

Notice that this formula is even simpler if the basis is orthonormal. Why is that?

QR Decomposition. If is a matrix in , then there is a matrix with orthonormal columns and an upper triangular matrix such that .

You can find the QR decomposition by applying Gram-Schmidt to the columns of and normalizing to get the columns of . Then compute .

We did the following examples.

Use Octave to find the QR decomposition for .

A = [1 1 6; 0 2 -3; -1 3 0];

[Q, R] = qr(A)Find the QR decomposition for .

Here is a video example with a tall-skinny matrix that we did not do in class.

Today we introduced the idea of floating point operations (FLOPs). Every time a computer needs to add, subtract, multiply or divide two floating point numbers, we count that as one flop. We also count every square root computation as one flop. This is a theoretical estimate of how long it takes the computer to calculate the operation.

After we got started with that workshop, we stopped to talk about computational issues with the Gram-Schmidt algorithm. We analyzed the following Octave code to perform the Gram-Schmidt algorithm.

function Q = cgs(A)

% Returns a matrix Q with orthonormal columns by applying

% the classical Gram-Schmidt algorithm to the columns of A.

[m,n] = size(A);

Q = zeros(m,n);

for i = 1:n

v = A(:,i);

for k = 1:i-1

v = v - (Q(:,k)' * A(:,i)) * Q(:,k);

end

Q(:,i) = v / norm(v);

end

endWe calculated that this algorithm requires flops for a matrix with rows and columns. Typically we only focus on the leading term, so we say that asymptotically the algorithm requires flops.

Unfortunately the Gram-Schmidt algorithm is numerically unstable. One way to show this is to start with an large ill-conditioned matrix , and then compute using the algorithm. The columns of usually won’t be orthogonal, which is a problem. We used the Hilbert matrix with entry equal to to show this.

n = 3

A = hilb(n);

Q = cgs(A);

norm(Q'*Q - eye(n))| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 16 | Least squares problems |

| Wed, Mar 18 | Least squares problems - con’d |

| Fri, Mar 20 | Orthogonal functions |

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 23 | Continuous least squares |

| Wed, Mar 25 | Fourier series |

| Fri, Mar 27 | Fourier series - con’d |

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Mar 30 | Numerical integration |

| Wed, Apr 1 | Newton-Cotes methods |

| Fri, Apr 3 | Error in Newton-Cotes methods |

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 6 | Numerical differentiation |

| Wed, Apr 8 | Review |

| Fri, Apr 10 | Midterm 2 |

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 13 | Eigenvectors and eigenvalues |

| Wed, Apr 15 | Power iteration |

| Fri, Apr 17 | Schur triangular decomposition |

| Day | Topic |

|---|---|

| Mon, Apr 20 | QR algorithm |

| Wed, Apr 22 | Singular value decomposition |

| Fri, Apr 24 | Applications of the SVD |

| Mon, Apr 27 | Last day, recap & review |